This recipe for “Cornish Cakes” caught my eye a few weeks ago when I was sitting in the reading room at the Huntington Library looking at mssHM 84007, a recipe book that was compiled in the last decade of the seventeenth century and the early decades of the eighteenth century. I was intrigued to see a recipe for a cake that began with claret, an imported Bordeaux wine, and called for mace, a spice made from the husk of a nutmeg, as its primary seasoning. The Cornish cakes that I prepared this weekend are sweet, purple-hued spice cookies.

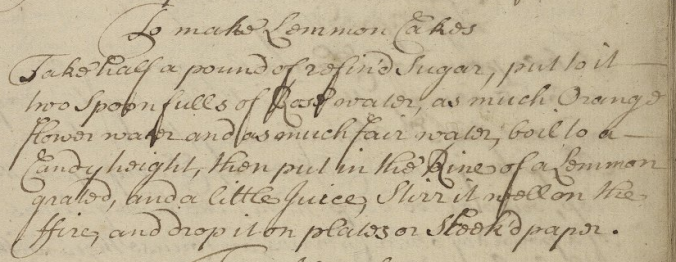

Original Recipe

Cornish Cakes

Take Clarret, and the yolks of Eggs, mace and

sugar and salt and mingle altogether in flower

knead them altogether then put in a Good

Quantity of Butter and knead it Stiff together

again.

[Huntington Library mssHM 84007, 85v]

I was initially curious to learn if Cornish Cakes were similar to any traditional Cornish recipes. Although my searches turned up many recipes for Hevva Cake (which I’m now eager to try), I did not find any traditional cakes that look like these — readers if you have any insights, please share!

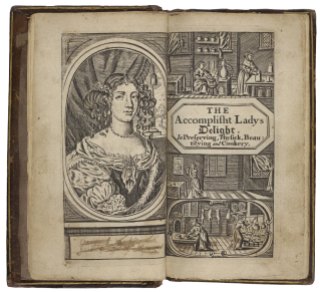

I did, however, find a similar recipe for “To make Cornish Cakes” in Hannah Woolley’s The Queen-like Closet or Rich Cabinet: Stored with all manner of Rare Receipts For Preserving, Candying and Cookery. Very Pleasant and Beneficial to all Ingenious Persons of the Female Sex (1670), G1v:

CXCII. To make Cornish Cakes.

Take Claret Wine, the Yolks of Eggs, and Mace beaten fine, and some Sugar and Salt, mingle all these with Flower and a little Yeast, knead it as stiff as you can, then put in Butter, and knead it stiff again, and then shape them and bake them.

Given the similarity in wording, it seems very likely to me that the compiler of mssHM 84007 copied their receipt for “Cornish Cakes” from Woolley’s printed cookbook sometime between the 1690s and the 1720s. The order of ingredients is the same and the verbs “mingle” and “knead” instruct the user to prepare the stiff dough. There are, however, some distinct differences. Woolley’s recipe calls for yeast and instructs the cook to shape and bake the cakes. The manuscript omits these details. (Learn more about Woolley’s cookbooks in this post and see other recipes I’ve adapted from her work here.)

When I got home to my kitchen and began to update this recipe, there were many variables to consider: what amounts of ingredients would create a “stiff” mixture? how much mace would create a pleasing spicy flavor? Mace is a lovely warming spice made from the membrane that surrounds the nutmeg kernel, but it can be quite intense. It is sold dried in fragrant blades and also sold ground. I also pondered: how much sugar should I add? how much sweetness would come from the wine versus the sugar (in 1690 , 1720, now)? The modern Merlot that I used in my recipe test is much drier than eighteenth-century claret. (I discuss claret and wine imports in more detail in this post.) Starting with a single egg yolk as my guiding proportion from the original recipe, I stirred together a rosy pink dough and tasted for spiciness and sweetness as I went.

Updated Recipe

This recipe made 12 spice cookies. Double or triple to make a larger batch.

1/4 cup (57.5 grams) red wine (such as Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, or a Bordeaux blend)

1 egg yolk

1/4 teaspoon mace

2 tablespoons sugar

1/8 teaspoon salt

1/2 cup (68 grams) flour

2 tablespoons (28.4 grams) butter

Take your butter out to come to room temperature. It should be soft and spreadable before you integrate it into your dough.

Preheat your oven to 350F (180C). Line baking sheets with baking parchment (or thoroughly grease).

Whisk together the wine, egg yolk, mace, sugar, and salt. Stir in the flour with a spoon. The dough will be a pink paste.

Add the butter. First stir with a spoon and then knead with your hands until well combined.

Shape small cookies (approximately 2 teaspoons of dough each) and place on the prepared baking sheets.

Bake for 15 minutes. The bottoms should be golden brown and the tops will still be light.

Allow to cool before eating.

As the cookies baked, the reddish pink color faded to a light purple — violet, light magenta as the light shifted. The fragrance of mace and wine wafted off them as they cooled. Like a mulled red wine, these Cornish Cakes are a sweet and spicy treat.

You must be logged in to post a comment.