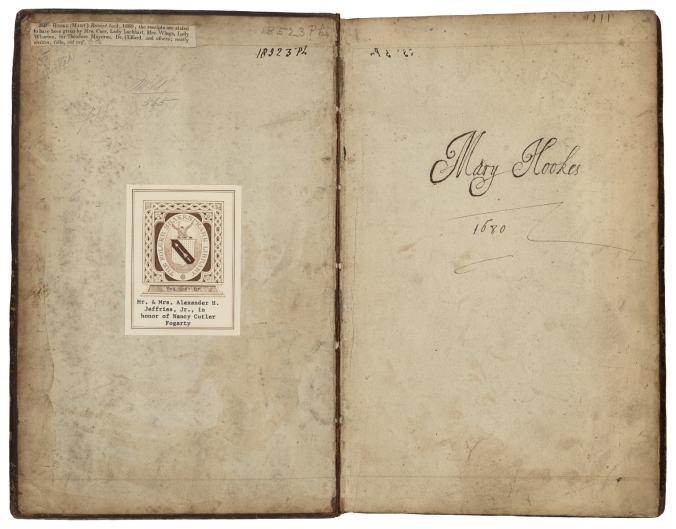

Since I love cooking with quinces at this time of year, I was eager to prepare this recipe “To Make Quince Cream” as part of my ongoing exploration of Christian Barclay‘s recipe book. In this post about a recipe to preserve quinces that I tried a few years ago, I wax poetic about the floral, fragrant quince as well as early modern and contemporary preserving practices. Instead of focusing on the fruit here, I’m going to consider the “cream.”

This recipe instructs a cook to stir cooled, cinnamon-infused cream into cooked, mashed, and sweetened quinces. It clearly explains the cooking method, but the recipe is short on measurements. A cook could add as much or as little cream as they preferred depending on their taste and the number of quinces that they were working with. They could also use this recipe to make a cream flavored with pears or wardens (a pear cultivar). In any case, sixteenth-, seventeenth-, and eighteenth-century English and Scottish cooks would have had access to an ample supply of dairy products to prepare creams.

Stephen Schmidt argues that creams specifically united rural and elite celebratory traditions in his post “What, Exactly, Was the Tudor and Stuart Banquet?” He writes that “Fresh fruits, cream, and local iterations of butter-rich cakes were typical treats of outdoor country festivals like May Day, which Robert Herrick frames as an idyll of ‘Cakes and Creame’ in his famed poem ‘Corinna’s Gone a Maying.’ The elite, meanwhile, enjoyed sophisticated dishes called creams in the lighter, sweeter, generally more delicate second course of dinner, which intermixed savory morsels like roasted songbirds, sauced lobster meat, and prime seasonal vegetables with creams and other sweets like gelatin jellies and fruit tarts.” Due to widespread dairy production, creams might accompany humble or decadent celebrations – with or without spices, fruit, or accompanying cakes. As Ken Albala writes, in The Banquet, “by the mid sixteenth century, cheese and dairy products had become a major item on banquet menus” and English cookbooks regularly included recipes for “dairy-based desserts” such as “trifles, fools, creams, and flummeries” (49). Creams fit into the Concordia discors of the banqueting table by offering a soft, rich, cooling (and, in this case, fruity) contrast to an array of spiced, sweetened, and savory dishes laid out at the same time. (I explore this concept further in my post on “Portugal Eggs.”) There are a number of recipes for “creams” that I’ve tested for this site that encapsulate this trend. Quince cream is a fitting recipe for a celebratory seasonal gathering in late autumn or early winter when the fruit is at its best.

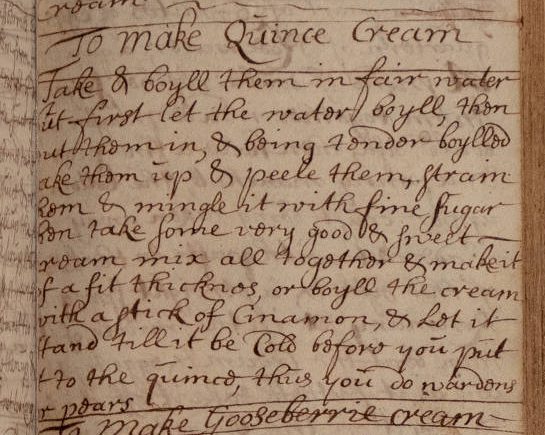

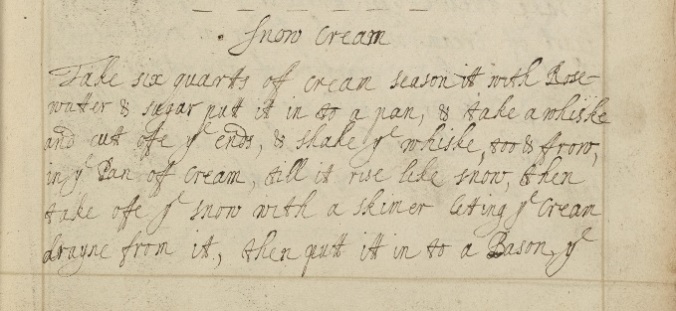

Original Recipe

To Make Quince Cream

Take & boyll them in fair water

but first let the water boyll, then

[p]ut them in, & being tender boylled

[t]ake them up & peele them, strain

[t]hem & mingle it with fine sugar

[t]hen take some very good & sweet

[c]ream mix all together & make it

of a fit thicknes, or boyll the cream

with a stick of Cinamon, & Let it

stand till it be cold before you put

[i]t to the quince, thus you do wardens

[o]r pears

Updated Recipe

2 small quinces (390g, 13.8oz)

1/4 cup sugar

1/2 cup cream

1 cinnamon stick

Put the whole quinces in a pot. Cover with water. Bring to a boil, then simmer for about 30 minutes or until the quinces are tender when poked with a fork.

While the quinces are cooking, put the cream and cinnamon stick in a pot. Bring to a simmer and then set aside and let cool.

Peel and core the cooked quinces. Mash them in a bowl. Stir in the sugar. Then stir in the cooled, cinnamon-infused cream.

The Results

The quince cream was sweet and floral with a hint of cinnamon. I found it quite rich, but pleasantly flavored. Although I ate it on its own, if I made it again I would serve it with a crunchy “cake” or cookie. My recipes for knotts, jumballs, or little cakes immediately come to mind. Let me know if you try this quince cream with an accompaniment or as part of a banqueting spread. (Let me know if you try it with pears (or wardens) instead of quinces, too!)

I would like to thank Clara Drummond, Heather Froehlich, Christina Riehman-Murphy, and my PSU Abington students for conversations about this manuscript that, in part, lead to me preparing this recipe.

You must be logged in to post a comment.