It’s soup season. I live in southern California and I have absolutely no complaints about winter weather, but I did get a good dose of cold when I visited Alyssa in Philadelphia this month to work on project planning and to prepare for our forthcoming profile in frankie magazine (out April 2015). In any case, who doesn’t enjoy a good bowl of soup?

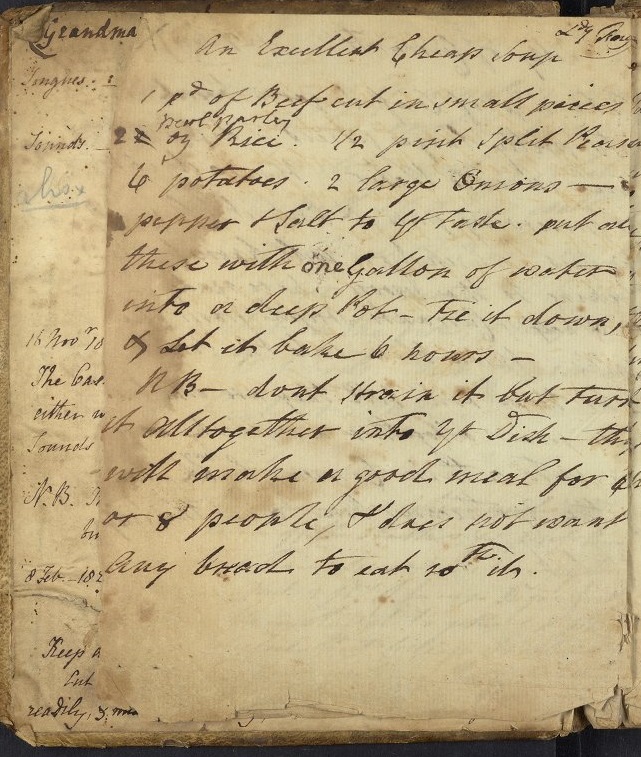

This recipe comes from Ms. Codex 644. Penn’s catalogers suggest that the manuscript was compiled between 1750 and 1825 and attribute this book primarily to a Lady Frankland with some additions in other hands. A note inside the front cover the manuscript entitles the volume “Grandmama Lady Frankland’s Receipt Book.”

This manuscript may be a product of the household of Sir Thomas Frankland, fifth baronet (1718–1784). This is a preliminary speculation, but one I hope to research in more detail. I’ve linked to wikipedia above because it’s freely accessible, but I’m also drawing on information from the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Sir Thomas Frankland married Sarah Rhett of South Carolina (1724-1808) in 1743 and she may very well be the “Grandmama Frankland” who compiled and used this recipe book. The family likely lived at the Frankland estate in Mattersey, Nottinghamshire while Frankland traveled between England and the West Indies where he was involved in the Atlantic slave trade, among other commercial ventures. The couple had many children (somewhere between thirteen and nineteen according to various accounts), and nine lived long enough to be mentioned in Frankland’s will. This recipe for cheap soup would certainly feed a crowd.

If this volume truly is a product of the Frankland family, my preliminary biographical research leaves me with many questions about the volume: What kind of history can these recipes possibly reveal? Can the volume provide a window into the history of slavery? Does it have anything to tell us about southern foodways, transatlantic communication, and global recipe exchange? For example, Frankland was born in the East Indies, possibly in India, and that connection to South Asia may explain the presence of a recipe for Indian Curry in the volume.

Stay tuned for more on Ms. Codex 644 as we continue to research its provenance and try out its intriguing recipes!

The Recipe

Lady Fagg

An Excellent Cheap Soupe

1 pound of Beef cut in small pieces

perl p[b?]arley

2 2 oz Rice. 1/2 pint split Peas

6 potatoes. 2 large Onions —

pepper & salt to the taste. put al[l]

these with one Gallon of water

into a deep Pot – Tie it down,

& Let it bake 6 hours –

NB – dont strain it but turn

it alltogether into the Dish – th[is]

will make a good meal for 6

or 8 people, & does not want

any bread to eat with it.

This is a straightforward recipe and it required minimal modification to work in my kitchen.

The soup recipe, like many others in the volume, is attributed to Lady Fagg in a small note at the top right corner of the page. Other sources noted in the manuscript include – Lady Monson, Lady Roche, Miss Colville, Miss Bedingfeld, Miss Bowles, Richard Jebb, Mrs. Cowslade, Baroness Philetsen, Dr. Addington, Dr. Bateman, Dr. Reynolds, and Dr. Darwell.

The final paragraph is a note that adds extra information to Lady Fagg’s recipe. “NB” stands for the Latin phrase nota bene, roughly translated as “take note.” This phrase that was used in books as a mnemonic aid to mark passages, thoughts, instructions for future use. It appears in many places throughout the manuscript.

Our Recipe

1 lb stewing beef, cut into 1-2 inch cubes

4 T butter, for browning beef

2 large yellow onions, chopped

2 oz pearl barley, rinsed and sorted

7 oz split peas, rinsed and sorted

6 potatoes, chopped into 1-2 inch cubes

cooking liquid: 1 cup chicken stock & 2 quarts water (This was the maximum amount of liquid my largest pot could hold. If you have a big stock pot, you should be able to accommodate a full gallon of cooking liquid. I recommend using 1/3 vegetable or meat-based broth and 2/3 water.)

salt and pepper to taste

Preheat your oven to 325F. Measure, chop, and prepare all ingredients.

Heat 2 T butter in an oven-safe stock pot or dutch oven. Brown the beef cubes in butter to seal-in their flavor. Add the other 2 T of butter as needed. When the beef is mostly browned, add the onions and allow them to soften for 1-2 minutes. Add the barley, peas, potatoes, and cooking liquid (stock and water) and cover. When the soup has come to a rolling boil, add salt and pepper to taste. Then transfer the pot to the oven to cook for approximately 2 hours. Check every 45 minutes or so to make sure the grains have not absorbed all the liquid and add water as needed.

The Results

This soup is tasty, warm, and filling. It could easily feed a large group or provide delicious leftovers for future meals.

The leftovers fed me, and my spouse Joseph, for a few meals. He even thought it tastier leftover because the flavors deepened. Although the recipe note insists that the soup does not need to be served with bread on the side, bread did make it a more substantial meal. Our batch produced ten servings (with bread) and if we’d had a larger pot we could have made an even greater volume. This soup is economical even in 2015 with its smart use of cheap cuts of beef and filling, healthy grains and legumes.

A sprinkling of fresh herbs like sage or parsley would add extra flavor to each bowl. I would suggest serving this soup on a cold night with warm bread, a green salad with a kale or spinach base, and a nice bottle of your favorite stout or porter.

You must be logged in to post a comment.