This post is adapted from an article that I published in a special issue of the Early Modern Studies Journal on Mary Baumfylde’s recipe book (Folger Shakespeare Library, call number V.a.456). Take a look at the whole issue here – Early Modern Recipes in a Digital World: The Baumfylde Manuscript.

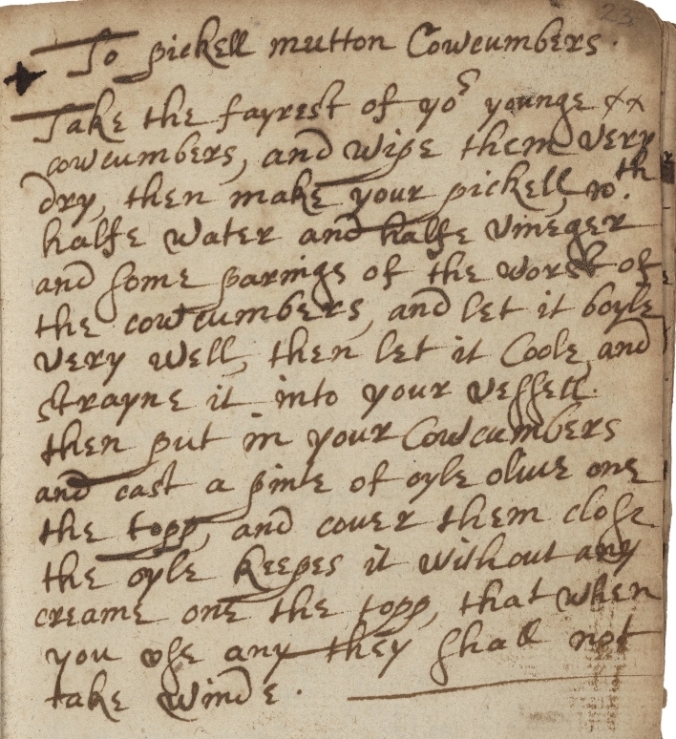

Recipes for preserved fruit and vegetables are ubiquitous in early modern recipe books. Mary Baumfylde’s recipe for pickled cucumbers (or “To pickell mutton Cowcumbers”) uses olive oil to form a natural seal between the outside air and the harvested vegetables (Folger Shakespeare Library, call number V.a.456).

Although we often associate preserving recipes with fruit and vegetables (jams, compotes, jarred sauces, pickles), Ken Albala reminds us that the “salted and sometimes acidic environment that inhibits bacterial growth” created by pickling brines can preserve “almost anything … including meats, vegetables, fish, olives” (Food in Early Modern Europe, 98). Pickling is an essential element of kitchen thrift and I’m pleased to share this pickle recipe early in the growing season before you find yourself with too many cucumbers on your hands.

To date, I have not found other references to “mutton cucumbers” in early modern books. Cucumbers were sometimes thought of as food only for livestock due to their undesirable humoral properties (described below). Hence the variant spelling “cowcumber” and perhaps the “mutton” designation used here.

The Recipe

To pickell mutton Cowcumbers

Take the fairest of your younge xx

cowcumbers, and wipe them very

dry, then make your pickell, with

halfe water and halfe vineger

and some parings of the worst of

the cowcumbers, and let it boyle

very well, then let it coole, and

strayne it into your vessell

then put in your cowcumbers

and cast a pinte of oyle oliue one

the topp, and couer them close

the oyle keeps it without any

creame on the top, that when

you use any they shall not

take winde.

The image of wind blowing into the pickling vessel and disrupting the contents is provocative. However, cucumbers are also potentially troubling in other ways. Renaissance dietaries frowned upon the cucumber because of its impact on the body’s humors. As Albala puts it, they were “[c]onsidered among the most harmful vegetables because of their cold and moist qualities, physicians usually recommended that they only be eaten in the summer by people who were naturally hot” (29). Pickling these potentially dangerous vegetables would have altered their cold quality through the addition of salt, sour vinegar, and spices. Although this recipe is not particularly spicy, other pickle recipes include long pepper, cloves, and fresh herbs.

Updated Recipe

10 small cucumbers

2 c water

1 ½ c white wine vinegar

½ c apple cider vinegar

1t salt

¼ c olive oil

Wash the cucumbers. Slice one. Arrange the others in a large, clean jar.

Bring the vinegar, water, sliced cucumber, and salt to a boil. Pour this brine over the cucumbers in the jar.

Pour ¼ c olive oil on top.

Let sit at room temperature for 24 hours. Then refrigerate. The pickles will keep for a few weeks using this method.

Delicious or dangerous, pickling helps cucumbers last beyond the harvest. Crunchy and sharp, these pickles are delicious alongside a sandwich or paired with cheese and charcuterie. The blend of apple cider and white vinegar creates a tangy, substantial brine.

Sealing the jar with oil appears effective at room temperature as well as in the refrigerator. I would hazard a guess that it worked at cellar temperature as well. I’d never thought to seal a jar this way and this piece of information about preservation was my major takeaway from preparing the pickles. Give it a try if you grow or buy too many cucumbers this summer!

You must be logged in to post a comment.