Photo by Carley Storm Photography http://www.carleystormphotography.com

It’s high time that we talk about jumballs. We were initially mystified by the moniker, but jumballs are a classic early modern treat: A rich, satisfying, highly-spiced, shortbread cookie. They are the single most delicious thing we’ve cooked from the archives to date.

Even a quick search to define the term revealed the jumball’s long-term popularity, from Gervase Markam’s classic English Housewife (1649) to the iconic Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management (1888), with examples on many other historical cookery sites like this one. The Oxford English Dictionary generalizes among the range of different spices and methods in these various recipes to define early modern jumballs as a “kind of fine sweet cake or biscuit, formerly often made up in the form of rings or rolls.”

In LJS 165 there are two recipes for jumballs back to back: “To Make Jumballs / My Mother Anges receipt” and “My Lady Chanworths receipt for Jumballs.” We thought that the first recipe’s mention of the compiler’s mother (or another source’s mother) was a poignant look into the perennial practice of handing down knowledge from mother to child, most likely mother to daughter. But the final instruction in that first recipe — soaking the baked jumballs in vinegar overnight — was not especially appealing, although it is very likely an excellent method for preserving the biscuits. Besides, who among us can take delicious cookies out of the oven and not eat them immediately? We decided to prepare the second recipe instead: “My Lady Chanworths receipt for Jumballs.” (If any readers try the alternate recipe, we’d love to hear how it turns out.)

The Recipe

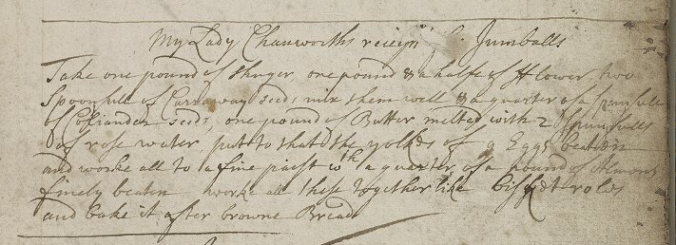

My Lady Chanworths receip[t for] Jumballs

Take one pound of shuger, one pound & a halfe of fflower, two

spoonfull of Carraway seeds, mix them well & a quarter of a sponfull

of Coriander seeds one pound of Butter melted with 2 spunfulls

of rose water, put to that the yolkes of 4 Eggs beaten

and worke all to a fine paist with a quarter of a pound of Almons

finely beaten worke all these together like bisket roles

and bake it after browne Bread

Like other sweet and savory recipes from the period, this recipe uses fragrant whole caraway and coriander seeds enlivened by aromatic rose water, the richness of egg yolks and butter, and the deep nuttiness of ground almonds. Other than halving the quantities in the recipe (which still made a lot of cookies) we’ve made no changes to the dough mix and simply reformatted the instructions into a modern style below.

Now, there are a wide variety of ways to shape jumball dough before baking. Recipes call for twisting, rolling, slicing, and folding. Given the texture of the jumball dough in a very hot kitchen (summer in Philadelphia) we decided to follow a classic shortbread method and to roll our dough into a long log, slice cookies 1/4 inch thick, and bake them. (If you try this recipe and shape them differently, send us a photo!)

Our Recipe

*Halved from the original. We also used a baking scale for this one, but we’ve included approximate volume measurements.

1/2 lb sugar (1c)

3/4 lb flour (2 3/4 c)

1 t caraway seeds

1/2 t coriander seeds

1/2 lb butter, melted (2 sticks or 16 T)

1 t rosewater

2 egg yolks, beaten

1/8 lb ground almonds (generous 1/2 c)

Preheat oven to 350F.

Mix flour, sugar, and spices in the bowl of a stand mixer (or a large bowl if mixing by hand). Add melted butter, rosewater, egg yolks, and ground almonds and mix until a uniform dough forms.

Place dough on a lightly floured surface and shape into cookies. We did this by rolling the dough into a log and slicing 1/4 inch cookies, but there are many other ways to shape this kind of dough.

Bake 20 minutes or until brown around the edges. Cool on a rack before devouring, if you have the willpower.

Results

They don’t look like much when you lift them onto the cooling rack (does shortbread ever look impressive?). But the aroma of spice and sweet gives it all away.

Jumballs are truly delicious. Their balance of nut and spice, fragrance and buttery texture is divine. They’d hold their own in a spread of cookies. We’ve since learned that they pair well with Italian Cheese, but we suspected from the beginning that they would complement vanilla ice cream, custard, fresh fruit, or a simple cup of tea.

When we shared these with unsuspecting friends they were bowled-over by the surprising and delightful presence of coriander. And their first guess was that we’d found the recipe on one of the latest trendy food blogs, not through this archival project. We’ll be making these again.

You must be logged in to post a comment.