This post draws on research from an article that I published in the collection After Print: Eighteenth-Century Manuscript Cultures.

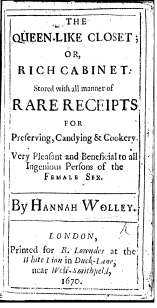

Hannah Woolley was an all-around lifestyle guru who not only wrote cookbooks, but also provided guidance on etiquette, homemaking, interior design. She even advertised her availability for private lessons to supplement her written advice with hands-on instruction. Although this recipe for “Portugal Eggs” comes from UPenn Ms. Codex 785, it was copied into the manuscript from Hannah Woolley’s The Queen-like Closet or Rich Cabinet: Stored with all manner of Rare Receipts For Preserving, Candying and Cookery. Very Pleasant and Beneficial to all Ingenious Persons of the Female Sex (1670). (Just like the recipe for “Lemmon Cakes” that I posted a few years ago when I first began researching this particular receipt book.)

portugal eggs

portugal eggs

To be honest, I could have used some further guidance from Woolley as I set out to prepare “Portugal Eggs.” I needed to make six sub-recipes in total to assemble this dish and four of these components needed to be made at least a day in advance. Without some modern tricks, such as using powdered gelatin for the jelly, this would have been even more labor intensive. That said, Woolley’s model housewife would have likely had a few of these components in her kitchen already.

Woolley title page

Woolley

This dish is perhaps most at home in a banqueting spread like one of these “Tempting Tables” set forth by Ivan Day. Indeed, it is listed among the many dishes served at the coronation of James II in A Complete Account of the Ceremonies Observed in the Coronation of the Kings and Queens of England (1727). It is visually striking, yet one of the strangest flavor combinations I have encountered so far in this project.

Although I’ve made this all sound very complicated (and it is) read on and let us guide you through one way a cook using Ms. Codex 785 might have prepared Woolley’s elaborate recipe.

The Recipe(s)

portugal eggs

portugal eggs

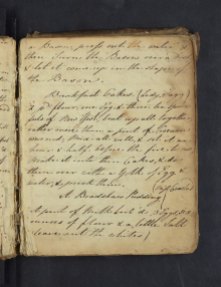

MS Codex 785

To make portugal Eggs

Take a very large Dish with a broad brim lay in

it some naples Biscake in the form of a star, then

put so much sack into the Dish as you think

the biscakes will drink up,on then slick them

full with little peices of preserv’d orange, and

green Citron peele, and strow Store of French

Comfits over them of Divers Colours, then butter

some Eggs and lay them here and there upon

the biscakes then fill up the hollow places in

the dish with severall colour’d jellyes and

round about the brim thereof lay Laurell

Leaves guilt with Leaf Gold, lay them slanting

and between the Leaves severall colour’d Jellies.

Hannah Woolley

XXXIX. To make the Portugal Eggs.

Take a very large Dish-with a broad brim, lay in it some Naples Bisket in the Form of a Star, then put so much Sack into the Dish as you do think the Biskets will drink up; then stick them full with thin little pieces of preserved Orange, and green Citron Pill, and strew store of French Comfits over them, of divers colours, then butter some Eggs, and lay them here and there upon the Biskets, then fill up the hollow places in the Dish, with several coloured Iellies, and round about the Brim thereof lay Lawrel Leaves guilded with Leaf-Gold, lay them slanting, and between the Leaves several coloured Iellies,

As both the manuscript and printed recipe make clear, “Portugal Eggs” are much more than an egg dish. When I decided to make this dish I began by deciphering the component parts: biscuits, candied citrus peel, “French Comfits” or sugar coated seeds, jelly, buttered (or scrambled) eggs, and gilded laurel leaves. Since the gilded laurel leaves were for presentation only, I decided to skip the gilding sub-recipe. I did, however, prepare the other five sub-recipes required to assemble the dish.

portugal eggs

portugal eggs

But first I needed to find recipes for all these components. This challenge initially puzzled me until I went back to the rare book reading room to inventory the entire manuscript. It seems to me that the compiler or organizer of Ms. Codex 785 might have been assembling sub-recipes for Woolley’s “Portugal Eggs” because the three recipes before it are for jelly and biscuits, two of the key components of the finished dish. All four of the recipes copied from Woolley’s cookbooks are in a single opening – two page spread – in Ms. Codex 785.

portugal eggs

biscakes

portugal eggs

portugal eggs

Guided by this proximity, I decided to use the recipe for “the best bisket Cakes” from Ms. Codex 785 as they are similar to other recipes for Naples biscuits (see “Artificial Potatoes” and “Bisket Pudding“). I also decided to try the recipe for “Jelly of Hartshorn,” which begins, as the name implies, with a deer’s antler. I started with packaged gelatin instead. For the other two sub-recipes I went farther afield. Although I experimented with Woolley’s own recipe for fennel comfits, I used a tried and true modern recipe for candied citrus peel. Any of these recipes might have made a great individual post, but today we are going to see what happens when they all come together.

1) Biscuits

To make the best bisket Cakes

Take four new laid Eggs, leave out two of the

whites, beat them very well, then put in two

Spoonfulls of Rosewater, and beat them very

well together, then put in a pound of double

refin’d sugar beaten and search’d and beat

them together one hour, then put to them

one pound of fine flour, and beat them

together a good while, then put them upon

plates rubb’d over with butter, and set

them into the Oven as fast as you can

but have a care you do not bake them

too much.

This recipe was relatively straightforward to update. It makes about 24 cookies.

4 eggs (2 whole, 2 whites only)

2 t rosewater

1 lb sugar (2 2/3 c)

1 lb flour (3 2/3 c)

butter or baking spray to coat the baking sheets

Preheat your oven to 350F. Grease two baking sheets with butter or your preferred baking spray,

Beat the eggs in a large bowl. I used a hand mixer for this, but a standing mixer would also work well. Add the rosewater to the eggs and continue beating. Add the sugar and beat on a high setting until the mixture starts to look fluffy (about 1 minute). Add the flour in three batches, allowing each to mix in fully.

Shape the dough into rough ovals. I did this by picking up about 2T of the dough and rolling it roughly in my hand. Make sure that you leave about a half an inch between the cookies, as they expand a lot as they cook.

Bake 15 minutes. The bottom of the biscuits should be nicely browned and the top still a little spongy.

Eat immediately with a cup of tea or allow to cool on a rack before storing.

2) French Comfits

Comfits are sugar coated seeds. Since Ms. Codex 785 doesn’t include a recipe for comfits, I turned to Woolley’s cookbook for a guide. Although I adapted Woolley’s recipe to coat fennel seeds in sugar, I could have also used this same method to candy coriander or caraway seeds. When I was at a local store, buying fennel seeds in bulk, I noticed a bag of modern-day comfits on the shelf. I threw some on the final dish for color and I’ve been snacking on them, too.

1/4 C sugar

1/3 C water

1T fennel seeds

In a small saucepan, bring the water and sugar to a boil.

A) Add the fennel seeds and simmer for 1 minute.

B) Strain the mixture to remove the fennel seeds reserving the sugar syrup. Spread the seeds out on a plate and allow to cool for 2 minutes.

Bring the syrup back to boil and repeat the straining and simmering steps (A and B) as many times as you like.

I did this three times before the seeds were too sticky to work with. The seeds were sweeter each time they came out of the hot syrup and cooled. Woolley suggests 8-10 coats of sugar. However, Woolley also instructs you to roll the hot seeds in the syrup with your bare hands. In any case, reserve the syrup at the end. I’m excited to add this leftover fennel-infused simple syrup in cocktails.

Allow the seeds to cool completely. Store them for future use.

3) Various Jellies

Inspired by the rich seasonings in the “Hartshorn Jelly” recipe, I prepared a lightly-sweetened jelly infused with lemon and cinnamon. This sub-recipe must be made well in advance because jelly needs to set in the refrigerator for at least three hours.

1 packet Knox Gelatin

1/4 C water

1/4 C sugar

the peel of one lemon cut into strips

1 cinnamon stick

3/4 C water

Sprinkle the gelatin over 1/4 C water in a medium-sized bowl. Set aside.

Place the other ingredients and 3/4 C water in a small saucepan. Bring this mixture to a boil. Once the sugar dissolves, reduce the heat to a simmer and allow to cook for another 3-5 minutes, until the mixture smells strongly of lemon and cinnamon. Discard the lemon peel and cinnamon stick. You can do this by scooping them out of the mixture or straining the whole thing and reserving the liquid.

Add the hot, fragrant liquid to the gelatin mix and stir to dissolve. Transfer your jelly mix to a flat-bottomed dish for easy shaping. I used a square, glass storage container for this.

Refrigerate for at least three hours before using.

4) Candied Citrus Peel

Given the complexity of the other components, I decided to candy my orange peel using this straightforward, twenty-first-century recipe.

5) Buttered Eggs

Buttered eggs are just an early modern way to talk about scrambled eggs cooked with butter and cream. You cannot make these in advance, so I have included the sub-recipe in the overall assembly instructions below.

Portugal Eggs

Once your jelly is set, your biscuits are baked, and your citrus peel and seeds are candied, you are ready to begin to assemble a dish of Portugal Eggs. The quantities below amply filled a standard dinner plate.

5 biscuits

3 oz sack (I used brandy, but sherry also works here)

1 T comfits (I used a mix of store-bought and homemade )

3T candied citrus peel

1 batch of buttered eggs (below)

4 T jelly (or more to taste)

2-3 sprigs fresh bay leaves to garnish

Buttered Eggs

2 eggs

3 T butter

3 T heavy cream

twist freshly ground black pepper

Arrange the biscuits in a star-shape on your dish. Pour about 3 oz of a spirit like brandy or sherry as a substitute for sack, a fortified wine. When the biscuits cannot absorb any more liquid, stop pouring. Set aside.

Prepare the buttered eggs. Whisk together the eggs and cream. Melt the butter in a frying pan. Add the egg mixture and stir the eggs until they are fluffy and cooked through to your preferred texture.

Return your attention to the main plate. Place comfits and candied orange peel on top of the soaked biscuits. You may, or may not, be able to stick your candied peel into the biscuits are the recipe suggests.

Add dollops of the eggs to the plate. In the remaining space, add spoonfuls of the jelly. Arrange the bay leaves around the edge of the plate.

Step back and admire your handiwork.

The Results

portugal eggs

portugal eggs

If I ever throw a feast using only recipes from this site, I’d make this dish again because it is truly beautiful. I might even spring for some gold-leaf.

That said, it’s one of the strangest flavor combinations I’ve encountered so far in this project. The boozy cookies pair nicely with the candied peel and fennel comfits, but clash with the rich eggs. It made me wonder about the perfect fork-full of this dish — Am I supposed to eat some eggs and then eat some sugary cake? Or am I supposed to eat a bit of everything in one cacophonous bite?

The lemon and cinnamon flavored jelly didn’t compliment any of the other flavors. Since the manuscript and print sources only insist on the various colors of jelly, but not the various flavors, a savory aspic or even an orange-flavored sweet jelly might be a better pairing for the eggs and seasoned cake. Perhaps the housewife or cooks using Ms. Codex 785 to prepare Portugal Eggs may not have used the “Hartshorn Jelly” after all.

This dish of eggs and sweets challenged, perplexed, and delighted me. Only by putting these items on the same plate did I finally grasp the variety, the mélange, intended in Woolley’s receipt copied into Ms. Codex 785. And only by thinking about this as a banqueting dish did it begin to make any sense at all. Banquets are about Concordia discors, variety, and performance—as are “Portugal Eggs.” I needed to experience the taste, smell, and sight of these eggs, biscuits, jellies, sugar sweets, and decorative laurels to make sense of their place in early modern food culture.

You must be logged in to post a comment.