This recipe “To Make Jumballs of Chocholett” is from Elisabeth Hawar’s recipe book (now William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, fMS.1975.003). A favorite on the banqueting table or dessert spread, many recipes for “Jumballs” or jumbles are collected in early modern recipe books. These small cookies are made from flour and almonds in varying proportions, sweetened with sugar, and flavored with anise, caraway, and, in this recipe, lemon, rosewater, and chocolate.

I was thrilled to return to the Clark Library last week to speak about my recipe recreation work, take a look at Elisabeth Hawar’s recipe book again (and other manuscripts), and to share this jumball recipe.

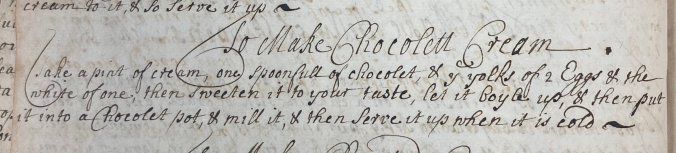

Original Recipe

(31) To Make Jumballs of Chocholett

Take halfe a ll of Jordan Almonds blanch ‘em in

warm water, & as you do ‘em put ‘em in cold water; have

ready some gum Dragon well steeped in water or rose

water, but the best is fair water & Juice of Lemmon

some Lemmon pill tenderly boyled, put your Almonds

into a Mortar, ffirst dry ‘em, beat ‘em to a very fine

paste, beat the Lemon pills with the Almonds, & as you

beat ‘em now & then put into them & a spoonful of

this water & Juice of Lemmon with the gum in it to

keep them from Oyling, when they are beaten very

small to a fine paste take it out of the Mortar & lay

it on a silver plate & set it on a little fire to dry

stirring it oft, then take some of this paste & work

it in fine sugar till it is a stiffe paste then roll

it thin, & cut it in little long pieces as you please &

make little Jumballs of some, & some put Chocholet

in & lay them on papers to dry before the fire,

a little will dry them.

The other part of the Almond paste which

you keep out take to it two spoonfulls of fine

flower & the white of an egge well beaten,

Mingle your flour & egge & Almond paste altogether

into a paste then make it up into little Jumballs as

you please in some of them put Chocholet, lay ‘em on

papers strew flour under them set them in a warm

Oven more than warm after you have drawn you

white bread out.

Let them be in the oven a little more than

a quarter of an hour.

The original recipe for Hawar’s chocolate jumballs is a complex, two-part affair. The first part provides instructions for blanching and grinding almonds in a mortar and a pestle to make an almond paste . Lemon peel and juice, rosewater, sugar, and “gum dragon” — dried, water-soluble plant sap used as a binder — help the freshly cooked and pulverized almonds form a paste. The second part of the recipe provides instructions for shaping jumballs out of this mixture with the addition of an egg white and flour. The pliable dough can be formed into pleasing shapes and gently, carefully baked as the oven cools from an intense period of bread baking.

As always, I’m committed to using ingredients that my readers can buy at their local grocery store (and rosewater). So I started with ground almonds and I did not buy gum dragon (commonly known today as gum tragacanth) to prepare this recipe. Since I’ve made marzipan in the past, I had a sense of what proportions I could use working from the 1 egg white called for in the recipe and felt fairly confident that I could get the mixture to bind. That said, starting with whole almonds and including gum dragon would likely impact the texture of the final jumballs. (If you make them this way, let me know!)

This recipe also insists on the tantalizing possibility of flavoring the jumballs with chocolate, but it does not provide a lot of detail about what that chocolate would be like. Hawar also included a chocolate option, with minimal explanation, in her recipe for puffs (meringue). I’ve worked with seventeenth-century hot chocolate recipes before and they helpfully provided me with some clues. To my mind, cocoa nibs are the least processed form of chocolate that is widely available in supermarkets today. In the half of my jumball dough that I flavored with chocolate, I decided to include both cocoa powder and cocoa nibs for crunch deep, slightly bitter chocolate flavor. Cocoa powder is a modern ingredient and an all-cocoa nib version would be rather different. (If you make a cocoa-nib only batch, let me know how it turns out!)

Updated Recipe

This recipe makes about 30 jumballs – half almond and lemon, half almond and chocolate. If you plan to make a batch of entirely almond and lemon jumballs, simply skip the final steps that describe dividing the dough and adding cocoa powder and cocoa nibs. If you plan to make a batch of entirely chocolate jumballs, add a double amount of the chocolate flavorings to the mix from the start (¼ cup cocoa powder and 2 Tablespoons cocoa nibs).

1 lemon, peel and 1 tablespoon juice

2 ¾ cups ground almonds

1 cup sugar

2 Tablespoons flour

1 egg white

1 Tablespoon rosewater

2 Tablespoons cocoa powder

1 Tablespoon cocoa nibs

Peel a lemon using a vegetable peeler. Place the lemon peel and 1 cup water in a small sauce pan. Bring to a boil and cook for 5 minutes. Drain and set the peels aside to cool. Chop the cooked lemon peel as finely as you can.

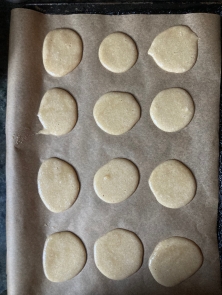

Preheat your oven to 350F (180C). Line two baking sheets with parchment paper.

Measure the ground almonds, sugar, and flour into a large mixing bowl. Stir to combine. Then stir in the chopped lemon peel and ensure it is evenly distributed throughout the mix. Add the egg white, rosewater, and lemon juice. Stir with a spoon and then with your hands. The mixture should hold together when pressed.

Divide the jumball dough in two in the bowl or on a cutting board. Place one half on a cutting board and the other half in the mixing bowl. Add the cocoa powder and cocoa nibs to the jumball dough in the bowl. Mix with a spoon and your hands until the chocolate flavorings are evenly distributed throughout the dough.

Shape the almond lemon and the almond chocolate jumballs on a cutting board and place onto the lined baking sheets. Letters, knots, twists, and other shapes using 1-2 Tablespoons of dough all work well. 1 Tablespoon balls of dough rolled smooth work especially well.

Bake for approximately 10 minutes. The bottoms of the almond and lemon jumballs will be golden brown and the jumballs will be crispy on the outside and soft in the middle.

Set aside to cool on a baking sheet for at least 5 minutes before serving.

The Results

Honestly, these jumballs are just delicious. They reminded me of all sorts of almond-rich, marzipan-like, European-style cookies that I’ve had the pleasure to enjoy near home or while traveling. The lemon peel lifts both the almond and lemon and almond and chocolate jumballs. Friends and family really liked these and I anticipate baking them again sometime soon.

You must be logged in to post a comment.