See the end of the post for information about the fourth annual Great Rare Books Bakeoff that is taking place this week (September 30-October 8, 2023)!

On a recent visit to State College, I was delighted to see a new addition to our recipe book collection. Lady Elizabeth Craven began to compile this recipe book in 1702 in the early years of her marriage and was still adding recipes to its pages at the time of her death in 1704, at age 25. There is much more to learn about Lady Craven and her manuscript and I was immediately interested in her fashionable recipe for “Chocolett Cream.”

As I’ve written in the past about hot chocolate and chocolate cream recipes, chocolate was a new and trendy ingredient in England that had recently arrived from the Americas in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Recipes for chocolate drinks and creams from this period reveal how Indigenous American knowledge about chocolate and the culinary preferences of Spanish colonizers shaped early uses of chocolate in English cookery. Lady Craven’s recipe typifies this trend as it instructs a user to “mill” chocolate or whisk it using a specialized chocolate whisk.

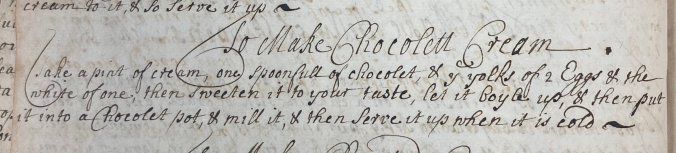

Original Recipe

To Make Chocolett Cream

Take a pint of cream, one spoonful of chocolet, & the yolks of 2 Eggs & the

white of one, then sweeten it to your taste, let it boyle up, & then put

it into a Chocolet pot, & mill it, & then serve it up when it is cold

Updated Recipe

1 pint (473ml) heavy cream

1 oz. (25g) baking chocolate

2 eggs

¼ cup sugar (50g)

Chop your chocolate into small pieces that will easily dissolve in hot cream.

Separate one egg and set aside one egg white. Whisk one whole egg and one yolk together in a small bowl.

Pour the cream into a small saucepan. Add the sugar, chopped chocolate, and whisked eggs to the pot. Heat over a medium heat until just simmering – about five minutes. Pay close attention to the pot to avoid overcooking and stir to prevent the eggs from solidifying on the bottom of the pot.

Remove the pot from the stove and pour the chocolate cream mixture into a sturdy bowl (or the bowl of a standing mixer). Beat with an electric mixer (or in a standing mixer, or by whisking vigorously) for about two minutes. (It will take substantially longer if you are doing this by hand.) The chocolate will fully integrate into the mix, small bubbles will form, and it will begin to look glossy.

Rinse out your saucepan and pour the chocolate cream mix back into the pot. Cook over a low heat for approximately ten minutes, whisking constantly. The cream will thicken and reduce in volume during this step.

Pour the hot chocolate cream mix into a storage container or heat-safe serving dish and allow to cool first at room temperature and then in the refrigerator for at least two hours.

Serve the chocolate cream cold.

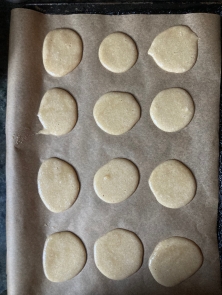

The chocolate is rich and luscious. I was surprised that this small amount of baking chocolate created such a deep chocolate flavor. As I eat the remaining chocolate cream in my fridge, I plan to pair it with fresh fruit, or maybe a warm fruit sauce, or simple sugar cookies or biscuits.

You must be logged in to post a comment.