Hippocras is a kind of spiced wine. As Paul Lukacs writes in his book Inventing Wine, wine drinkers at all levels of society in medieval and early modern Europe drank spiced wines, “Spices not only would disguise a wine beginning to turn bad but also could make an otherwise dry wine taste somewhat sweet. And medieval men and women craved sweets. They used cloves, cinnamon, honey, and the like to season” their wines and their foods (43). Wines made before the invention of modern bottling technologies were highly perishable and markedly different from the wines we drink today. According to Lukacs, some were made from raisins and fermented to be sweeter and almost syrupy in texture, others were thin and sour depending on age and style. Fresh from harvest in the autumn, cloudy and fragrant wines were shipped in huge volumes from France, Italy, Germany, and later Spain to wine-consuming countries such as England which did not (at that time) have a local wine industry of its own. Adding spices to these wines as they aged made them more palatable and also added health benefits from the spices themselves. After the wine was infused with spices and sweetener, but before it was served, it was strained through a linen “hippocras bag” to remove the spices and other flavoring. This linen bag was named after Hippocrates, the ancient physician who advised the consumption of spiced wine drinks and was thought to have strained them through his voluminous sleeves.

hippocras

hippocras

I’m excited about this post because I developed a hippocras recipe that I think is truly delicious and I learned a lot along the way. After many hours in the reading room at the UPenn library and many more hours clicking through digital images of manuscripts and printed books online looking for Hippocras (or its variant spellings Ipocras , Ypocras, Hypocrass, Hippocris, and Hipocras), I decided to prepare a recipe “To make Ipocras” from Robert May’s The accomplisht cook, a very popular cookbook that was first published in London in 1660. I’ve been thinking about May quite a bit over the last six months and I updated another recipe from this cookbook for the upcoming exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library, First Chefs: Fame and Foodways from Britain to the Americas. (Stay tuned for that recipe!) May’s Ipocras recipe beautifully seasons the wine without eradicating the original flavors. This was especially important to me because I was using a wonderful 2016 Côtes du Rhône made by Clovis thanks to T. Edward Wines. The wine is delicious on its own and I knew, with proper care, it would make a delicious hippocras as well.

hippocras

hippocras

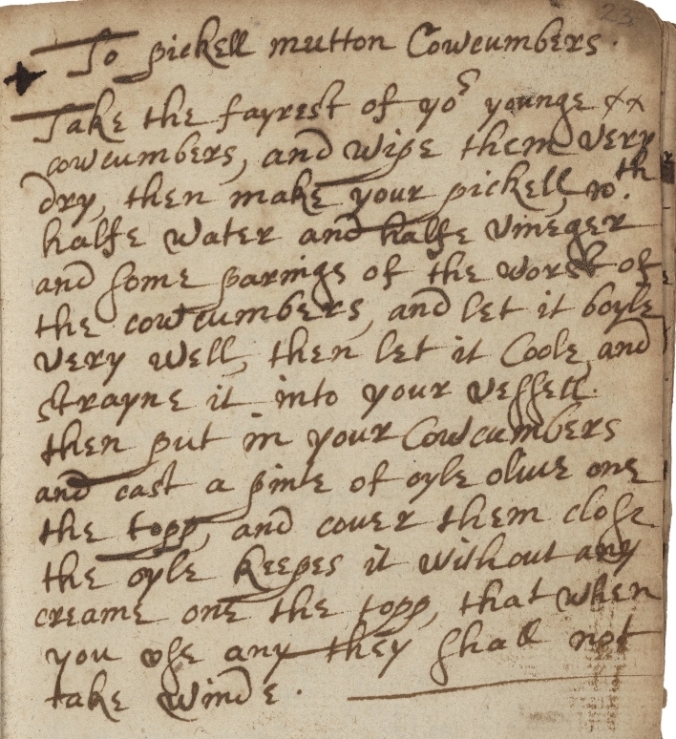

Below, you will find May’s recipe, my updated version of it, and quite a few hippocras recipes from manuscripts at the Folger Shakespeare Library, Clark Library, and UPenn Library. These recipes showcase a range of methods and I’ve including images and transcriptions below. I might make them someday, but feel free to experiment and let me know how things go in the comments.

May’s Ipocras Recipe

To make Ipocras.

TAke to a gallon of wine, three ounces of cinamon, two ounces of slic’t ginger, a quarter of an ounce of cloves, an ounce of mace, twenty corns of pepper, an ounce of nutmegs, three pound of sugar, and two quarts of cream.

Otherwayes.

Take to a pottle of wine an ounce of cinamon, an ounce of ginger, an ounce of nutmegs, a quarter of an ounce of cloves, seven corns of pepper, a handfull of rosemary flowers, and two pound of sugar.

Robert May,

The accomplisht cook,

or The art and mystery of cookery. Wherein the whole art is revealed in a more easie and perfect method, then hath been publisht in any language. Expert and ready wayes for the dressing of all sorts of flesh, fowl, and fish; the raising of pastes; the best directions for all manner of kickshaws, and the most poinant sauces; with the tearms of carving and sewing. An exact account of all dishes for the season; with other a la mode curiosities. Together with the lively illustrations of such necessary figures as are referred to practice. / Approved by the fifty years experience and industry of Robert May, in his attendance on several persons of honour. (London: Printed by R.W. for Nath. Brooke, at the sign of the Angel in Cornhill, 1660),

Wing M1391. Photo courtesy of the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts. (T3r).

I decided to follow May’s instructions for “Otherwayes … To make Ipocras.” As I show below (and you can see above in May’s first recipe), many Hippocras recipes are intended for white wine, add sack, or use milk or cream during the straining process. May’s “Otherwayes” showcases the characteristics of the original wine as well as the added spices.

May’s Ipocras Updated

1 bottle red wine (ideally an earthy Côtes du Rhône like this one from Clovis)

4 cinnamon sticks

2-inch piece of fresh ginger, sliced

2 slices of a whole nutmeg, or 1/4 t ground

4 whole cloves

4 black peppercorns

2 springs fresh rosemary

1/3-1/2 c sugar (optional, I preferred it without)

Combine the wine, spices, and sugar (if using). Cover tightly and let infuse at room temperature for 24 hours before you plan to serve it.

Strain out spices before serving using a metal or cloth strainer.

The first scent that reaches my nose is rosemary, then cinnamon, then the aroma of the wine itself. The cloves, pepper, and nutmeg all appear in the first sip. Within hours of first pouring it, the hippocras was all gone. The neighbors that stopped in to taste it loved it. One likened it to a brandy cocktail. Another thought the spice flavors were similar to Charoset, the fruit paste from the Passover seder. We all preferred the unsweetened hippocras. In this, we are probably unlike May’s original audience who had quite a sweet-tooth.

Other ways to make Hippocras

May’s recipe adds the flavors of spice and sweetness to red wine. Other Hippocras recipes take a range of approaches. I’ve also recently tested Mary Baumfylde’s recipe for

White Hippocras from Folger V.a.456 for another essay I’m working on. This recipe uses a “

milk punch” method to clarify and strain the hippocras. After the initial infusion, milk is added. It curdles and the curdled milk solids are strained out along with the spices. This made a very tasty drink, but I could not taste any of the characteristics of the wine at the base. These hippocras recipes below are all promising, but all showcase fewer of the original wine’s characteristics due to the addition of lemon juice, other alcohol such as sack, or milk.

This white wine and sack Hypocrass is from Elisabeth Hawar’s recipe book now held at the

Clark Library in fMS.1975.003. It is likely that Elisabeth, or another owner, lived in East London as the book includes manuscript directions to places in Shoreditch and Spitalfields.

To Make Hypocrass

Take 3 pints of white wine & a quart of Sack & a

pinte of milk, Sinamon 2 oz Ginger 1 oz of Nutmegs

2/1 an oz beaten of Cloves halfe a pennyworth, 2 t of

powder shuger or else all the spice & shuger must be

steeped in the Sack all night, Red Rose water 6 spoonefull

one bunch of Rosemary & 3 bay leaves lett it run throw

a bagg till it be as clear as rock water

This recipe from Judith Bedingfield’s manuscript at UPenn (Ms. Codex 631) is driven by orange flavors, includes apples (pippen), and uses the milk punch method. The wine infuses with the sweetness and the spices and once the milk is added it curdles. When the curdled solids are removed, the mixture is clarified and flavorful.

To Make good Hippocras, red or White

To Make the Quantity of two Quarts, you must take two Quarts of good French White Wine

or Red Wine is much better if it be of a very good Red: on the said two Quarts of wine you’ll

put a Pound of Loaf sugar, the Juice of two Lemons, seven or eight thin Slices of Sevill

orange peel, if you have any Portugal Oranges you’ll put in the Juice of one, with ten

or twelve Zests, or thin Slices of the Peel of the same Orange. if you have none there needs

none. you’ll put also on the said two Quarts of wine one Dram of Cinnamon broke a little

four Cloves broke in two, a Leaf or two of mace, five or six Grains of White Pepper, half

broken, & a small handful of Coriander seeds, also half broken or beaten, half a golden Pippen

or, if small, a whole one, peel’d & cut into Slices, & half a Pint of good Milk: then stir them

well together with a spoon, & strain it through a clear straining Bag, untill it comes clear;

& when it is very clear & transparent, make it run into a jug or any thing else that you’ll

cover with a strainer (that is named Stamine) & so let it run through that into your jug:

then take, on the Point of a Knife, some musk & Amber Powder. #

Alternatively, this recipe from UPenn LJS 165 uses all sack, a sweet wine from Spain or Portugal and precursor to modern sherry.

Hippocris to make

Take 1/2 a pound of Curran seed 3 ounces of long pepper

6 ounces of Cinamon: 2 Ounces of ginger 1 ounce of Nutm[eg]

a Sprig of Rosemary a Lemon Sliced 6 quarts of of Skimed mi[lk]

but not Sower, 6 pound of cleane suger 6 gallons of sack steep

(but the Milke and suger) in the sack 6 dayes Stir it twice or th[xx]

a day put it into a large Tub & poure in the Milke leasurely th[xx]

stirring the sack very fast putting in the suger into the Tub before

let it run through the bag

Lady Grace Castleton’s recipe book Folger Ms. V.a.600 includes a receipt “To make Hipochras” from a “Lady Cauendishe.” This version includes cardamon and, like the previous examples, starts with white wine and is strained with milk.

To make Hipochras L[ady] Chauendishe 85

Take a pound of white lump sugar, two ounces

of symonan, a quarter of ounce of gingar, &

a quarter of an ounce of cloves, bruse these

spices, & put them with the sugar to steep in

a gallon of good white wine, stir them

well together, & lett them stand all night clos–

covered in astone pott, in the mourning putt

halfe a pint of new milk in’t, & lett it run

through a jellye bagg, wetting it first in

milk & wringe it out again, Lett it

run through the bag, soo often till it be cliar

& taste stronge of the spices, a few cardemum

seedes a mongst the spices will give it agood

taste.

Hippocras took many forms. Enlivened with spices and fruit, enhanced with strong sack, or tempered with dairy, Hippocras recipes were designed to healthfully and deliciously amend premodern wines. Despite what Lukacs and others suggest about early modern cooks using spices to amend spoiled wines, the Castleton and Bedingfield recipes insist on starting with good wines. That way, the resulting spiced wines will be as delicious and efficacious as possible.

Special thanks to Daniel Veraldi and T. Edward Wines for supplying the Clovis 2016 Côtes du Rhône.

You must be logged in to post a comment.