I first learned that a “codling” was an unripe apple from the footnotes in a copy of William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night. When Cesario arrives at Olivia’s gate and refuses to leave, Malvolio turns to ambiguous metaphors to describe the persistent youth to his mistress:

Not yet old enough for a man, nor young

enough for a boy—as a squash is before ’tis a

peascod, or a codling when ’tis almost an apple. (1.5.155-157)

A codling is almost an apple, like a boy is almost a man. The Oxford English Dictionary records both the literal and metaphorical definitions of “codling” — “Originally: an immature or unripe apple; a type of hard apple suitable only for cooking” in medieval and Renaissance usage, and, later, in Shakespeare’s lifetime, “figurative. With implication of immaturity or inexperience: a young man, a youth. Obsolete.”

A few weeks ago, I had a bowl of freshly picked codlings in my kitchen. My spouse Joseph planted apple trees in our back garden back in 2021 and this year they have fruited for the first time. The codlings were in the kitchen because he had carefully thinned the fruit clusters to allow the largest fruits on each tree to grow larger.

Seventeenth-century recipes that call for codlings were likely crafted to turn this early harvest of unripe fruit into a delicacy. The codling tarts that I prepared from Jane Parker’s 1651 recipe book, now Wellcome, MS.3769, are a tasty product of preservation and thrift.

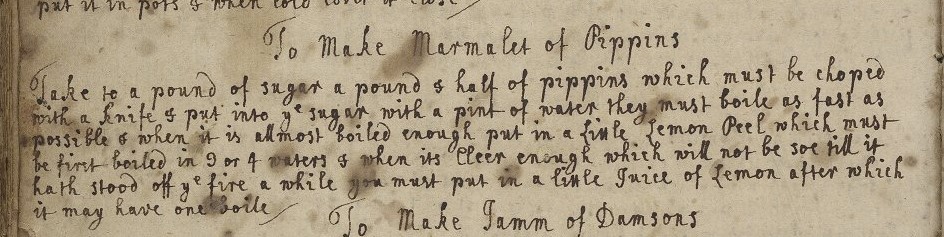

Original Recipe

to make a codling tarte

codle the appells, pill and cut the pape from the cores, and

put as much of that pape into some cream as

will make it thicke, put in a litell genger sinamon

and suger and rosewater, then bake it (18r)

After gently cooking the unripe apples, the recipe instructs you to peel and core them, to mash them to a pulp, and stir them into a tart filling fortified with cream and seasoned with ginger, cinnamon, sugar, and rosewater. The recipe implies that you already have pastry to hand to pair with the tart filling.

Parker’s recipe also reveals the confusing linguistic overlap between “codling,” an unripe apple, and the verb “to coddle,” a method of gentle cooking. The codlings must be coddled before they can be consumed.

Updated Recipe

A pint container of codlings yielded 1 cup of codling pulp after cooking, peeling, coring, and mashing.

Use your preferred pastry. I used just shy of half of Mark Bittman’s classic pie crust recipe to make two small tarts baked in 5-inch tart pans.

2 cups codlings

water for boiling

1 batch pastry

butter or cooking spray to grease your tart pans

2 Tablespoons heavy cream

1/4 teaspoon ground ginger

1/4 teaspoon ground cinnamon

1/4 cup sugar

1 Tablespoon rosewater

Put the codlings in a pot and cover them with water. Bring them to a boil and reduce to a simmer. Cook for about 12 minutes. The apples should be tender when poked with a fork.

Pour off the water. Set the cooked codlings aside and allow them to cool. Remove the skin off with a peeler and your fingers. Quarter the codlings and remove the cores. Put them into a bowl. Mash the codlings into a a rough pulp using a potato masher and a fork. (Some larger pieces remained in my mixture and I did not mind them.)

Prepare your pastry. Butter your tart pans and line them with pastry.

Preheat your oven to 350F.

Add the cream, ginger, cinnamon, sugar, and rosewater to the codling pulp. Stir until combined.

Fill the tart shells with the codling filling. Place them on a baking sheet.

Bake for 30 minutes. The filling should be caramelized and set, but still jiggle slightly in the middle.

Allow to cool for at least 10 minutes before serving.

The tarts were tart and well-spiced. Codlings are far more sour than ripe apples. This recipe is designed so that the sweetness of the sugar, the seasoning from the spices and rosewater, and the fat from the cream and buttery pastry balance out the inherent sharpness of the codlings.

Although I liked the shape of these tarts, I wondered if the codling filling might also be used to fill free-form galettes or even baked without a pastry crust.

If you find yourself with codlings this season, this recipe is a great way to use them.

You must be logged in to post a comment.