Last week, Marissa and I were very pleased to give a talk on “Shakespeare’s Kitchen” at the Folger Shakespeare Library, part of its Free Folger Friday series. Good timing: the foundations of Shakespeare’s kitchen area at New Place in Stratford-upon-Avon were discovered by an archaeological team (!) just the week before. We cooked up a few new recipes for the event. Now, it’s been suggested that I might be a rabid fan of the Christmas season. I think I’m just enthusiastic. (Typed while looking at the decorated pine branches on my bookshelves [my version of a tree] and listening to Bing Crosby. Ok, fine. Very enthusiastic.) So, we decided to be seasonally festive with these recipes. Along with the (awesome) hot chocolate mix that Marissa will be sharing soon, we investigated early modern gingerbread.

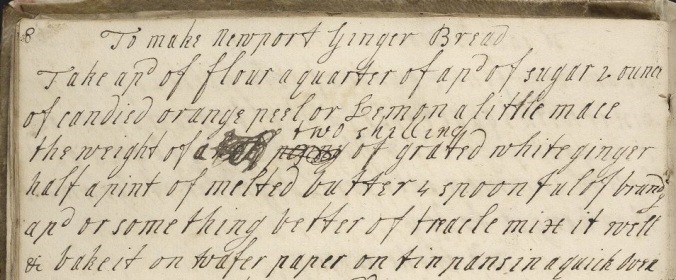

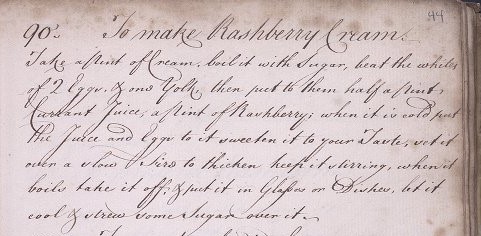

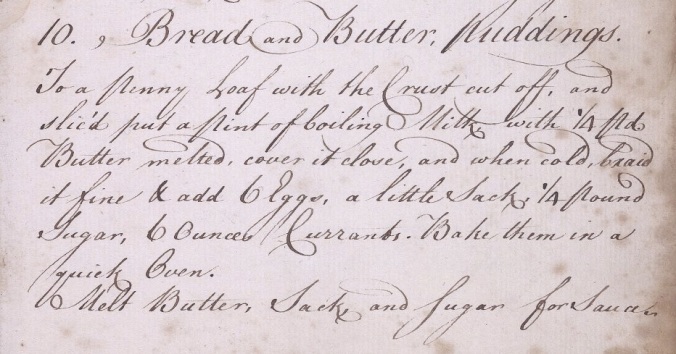

For the gingerbread mission, I turned to a new – to us – recipe book: UPenn Ms. Codex 214. Both the front and back covers are embossed with the original owner’s name, and the inscription includes a date, so we know that the book originally belonged to Catherine/Catharine Cotton and was compiled starting around 1698. We’ll definitely be revisiting this collection, which contains a range of appealing recipes – including the poached apples I have my eye on next. Cotton’s book turned out to be well-suited to this particular mission, as it contains three gingerbread recipes: one with honey and candied peel, one with brown sugar and milk, and one with treacle and caraway seeds.

Gingerbread as a dessert began appearing in Europe around the fifteenth century, originally as a mixture of breadcrumbs held together with honey and ginger, then shaped using molds. At Queen Elizabeth I’s court, gingerbread was baked into the shape of people and decorated to look like visiting foreign dignitaries – the first gingerbread men! In the late seventeenth century, ginger would have been imported into England (most likely from Jamaica, the Spice Islands, or India) as the whole root, sometimes pickled. That Cotton’s book includes not one but three recipes for gingerbread indicates ginger’s availability and the treat’s popularity by 1698.

The Recipes

To make ginger-bread Mrs JT

Take 2 pound of browne sugar put to it a pound and a quarter

of butter & half a pint of milk tset it to the fier and amake it

just warme enough to melt the butter then take sume flower & put to it

and 3 ouncis of ginger so make it up in a stif paste /

To make good Gengerbread P.C.

Take 3 pound of fine flower meix with it a pound

of sugar 2 pound of good honey an ounce and a half

searced Ginger some candyed orange and lemen peils

put all these together melt your honey & mould it well

then make it into littel caks & bake it as soon as you

please but your oven must not be hotter then for Biscakes

mwhen you have done all this let your humble saruant

have good share

Our Recipe: “To make ginger-bread”

[quartered from original*]

1 1/4 c. brown sugar

10 tsp. butter

1/4 c. milk

2 c. flour

3/4 oz. fresh ginger, peeled and minced (about 1″ ginger root)

Combine sugar, butter, and milk in medium saucepan and cook over low heat, stirring frequently, just until butter is melted. Remove from heat. Add ginger, then stir in flour in two batches.

To use immediately**: Scoop dough in tablespoon-sized balls. Flatten slightly with fingertips or bottom of a water glass.

To roll out***: Pat dough into a disc, wrap in plastic, and refrigerate at least 2 hours or overnight. Roll to 1/4″ thickness on a floured board and cut out in shapes.

Both methods: Bake at 350F for 12 mins., until bottoms are golden brown. (Tops will look slightly puffed but won’t take on much color.) Remove from baking sheet and cool on a wire rack. Makes ~2-3 dozen cookies.

*I halved the recipe and ended up drowning in gingerbread cookies – over 50 of them! Quartering the recipe makes for a more reasonable yield, but it can easily be scaled back up if you’re in need of gingerbread for days.

**The recipe implies that the dough can be used right away. However, I’d added enough flour that it was starting to taste bland and the dough was still fairly soft and sticky. I knew I wouldn’t be able to roll it out, so I scooped it into balls and experimented with flattening some of them. The flatter the discs, the better they baked – the scoops left round didn’t have the nice bite that the thinner cookies did.

***”Paste” can stand in for our modern “pastry” in these cookbooks, so it didn’t seem unlikely that the original could have been rolled and cut out. To manage this, I refrigerated the dough, which made it much easier to handle. In fact, it rolled and baked up beautifully – this is definitely my preferred method for this recipe.

Our Recipe: “To make good Gengerbread”

[quartered from original]

2 1/2 c. flour

1/2 c. sugar

1 c. honey

~1 c. candied peel (2 oranges + 1 lemon), roughly chopped****

Combine flour, sugar, and honey in a large mixing bowl, using a spatula or (as I did) your hands. Add the peel and make sure it is evenly distributed through the mixture. The dough will be very crumbly.

Using a scoop or soup spoon, take about 1.5 tbsp. of dough at a time and squeeze/pat it into a flattened ball. Bake cookies at 350F for 15-18 mins., until lightly browned and fragrant.

****Candied peel is an ingredient we run into frequently in these early modern recipes. As we’ve discussed with some readers, candied peel is readily available in British supermarkets but not in most American ones, so we sometimes end up substituting zest to approximate the taste (if not texture) of the citrus peel. For the gingerbread, however, I wanted to see how the peel would work with the ginger and also thought the sticky peel might help these crumbly cookies hold together, so I made my own using this recipe.

The Results

One winner, one respectable second-place finish! The “ginger-bread” gingerbread was surprisingly flavorful, given its short list of ingredients: there’s a LOT of sugar and butter and ginger in there, but they all meld well together, perhaps mellowed by the addition of milk, and these were neither overwhelmingly sweet nor too gingery. (I might even increase the ginger next time, maybe throw in 1/2 tsp. of powdered ginger to add some bite.) As noted above, I experimented with making these into balls, discs, and cut-out cookies. They all worked, but the cut-out cookies baked uniformly and had a good bite while retaining some softness. I’ll use this method from now on.

The “Gengerbread” gingerbread turned out to be tasty toothbreakers. Because the original recipe suggests melting the honey, I’m guessing that honeycomb might have been used here, and that the wax would have helped as both a binding and softening agent. I didn’t have any honeycomb, but I did have an old(ish) jar of honey waiting to be used – good enough. I had to add slightly more honey than called for to get the dough to hold together. They were still fairly dry and VERY hard. (I made them in two sizes and found the smaller cookies even more difficult to bite into than the larger ones!) Some gnawing was require on the first day, though they softened over the next few days. (And, as was helpfully suggested at the Folger talk, you could put a slice of bread or apple in the container with them to speed this softening process.) I like the candied peel + ginger combination very much – in fact, you taste the honey and the citrus more than the ginger here, which is interesting. I probably won’t be making these exact cookies again because I’m not sure my teeth can handle it, but I might play with adding honey and/or candied peel to some other gingerbread recipes.

Will I abandon the family gingerbread recipe that I make every year? Not a chance. But making these two recipes – I’ll report back on the third once I acquire some treacle – introduced me to some new gingerbread ideas and highlighted the variety available in just one recipe book. And the room to play with different techniques. In this project, not being given a specific method can nerve-wracking – particularly for someone who likes to follow very precise baking instructions. (See: me.) But it’s also liberating. There’s room for creativity, fun, and experimentation in the ambiguity. I’m looking forward to seeing what else is in Cotton’s book. Stay tuned.

You must be logged in to post a comment.