This post was first published on the Folger Shakespeare Library’s blog Shakespeare in Beyond: “Love-in-idleness, Part One: Adapting an early modern recipe for heartsease cordial”

You can also read more about heartsease in Shakespeare’s play A Midsummer Night’s Dream in a second blog post that I wrote for the Folger: “Love-in-idleness, Part Two: Intoxicating botanicals in A Midsummer Night’s Dream“

Pansies were intertwined with matters of the heart – both lovesickness and cardiac ailments – linguistically, in the herbal tradition, and in recipe manuscripts that were created and used by early modern households as repositories of culinary and medicinal knowledge. The etymologies of the various names for this flower – pansies, heartsease, and love-in-idleness – attest to the connection between the botanical and the medical.

Common understandings of the body in Shakespeare’s England were rooted in humoral theory in which bodily and emotional health were deeply intertwined with the natural world. Discussions of the names and uses of flowers for healing physical and emotional ailments in herbals, practical handbooks, and recipe collections derive, in turn, from humoral thinking.

The English translation of Rembert Dodoens’ A nievve herball, or historie of plantes (1578) explains that the pansy flower is called, “in English Pances, Loue in idlenes, and Hartes ease: in Frē[n]ch Penseé” from which pansy – here “Pances” – derives and conveys the sense of pensiveness or musing (p.148, sig. Aiiir). Heartsease is also a descriptive name that captures the flower’s capacity for promoting well-being by easing ailments of the heart such as grief. The name “loue in idlenes” carries the common connotations of frivolity, emptiness, or time-wasting, but also would have conveyed a sense of love-sick idleness characterized by folly, foolishness, or delirium.

In their herbals, Dodoens and John Gerrard largely concur in their description of the virtues – or medical applications – of cordials and tonics derived from pansies, recommending them to treat ailments of the chest and lungs as well as fever and inflammation. Gerrard suggests that heartsease might also be used in the treatment of the “French disease” or syphilis, which was known to be a sexually transmitted infection in the period. Mary Floyd-Wilson writes that “[i]ts purple color places it among the venereal plants—those herbs ruled by Venus” (187).

Heartsease and pansy both appear in early modern recipes for healing waters that involve infusing herbs and flowers in alcohol and then distilling the liquid in an alembic and sweetening the concoction with sugar before giving it to a patient.

A list of medicinal “Cordialls” in a 1675 recipe manuscript compiled by Thomas Sheppey (and now Folger MS V.a.452) begins with a recipe for a preparation of pansies and sugar “To clear the heart.” Derived from the Latin word for the heart, cordis, cordials treat the heart in both the physical and emotional sense.

The Recipe

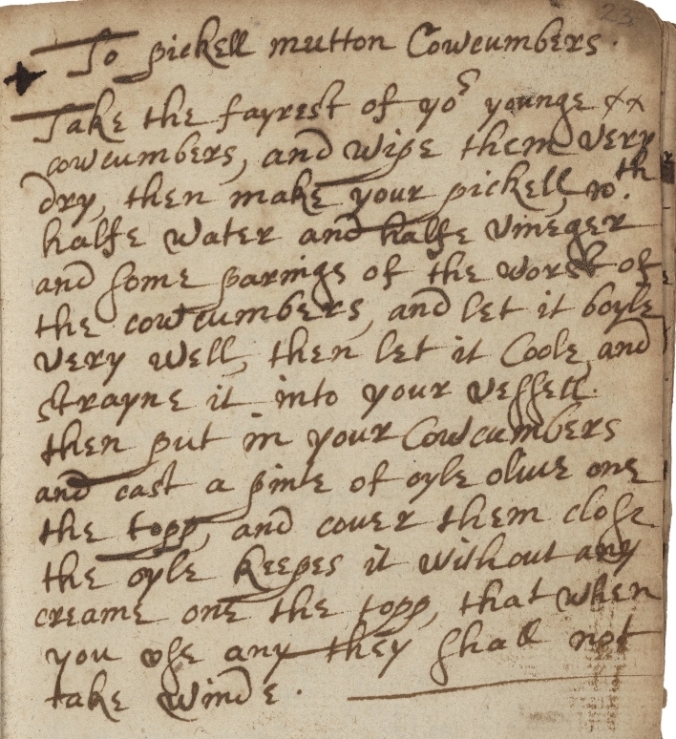

CAPTION: “Cordialls.” from Thomas Sheppey’s recipe book, Folger Shakespeare Library, V.a.452, page 75. https://luna.folger.edu/luna/servlet/s/24ms0t

To clear the heart. Take a quantity of heartsease, and putt

therto 3 times the quantity of sugar. make a conserve, and

take therof when you are sad. MS.

While this cordial could “clear the heart” in the same sense that Dodoens and Gerrard used – to treat the chest and lungs or to reduce fever – it could also potentially heal heartache and other amorous ailments: The verb “clear” can mean to brighten, enlighten, and purify as well as to remove obstructions. The dosing instruction in the recipe “take therof when you are sad” suggests that the sad – in the sense of someone who is serious, somber, or weary, as well as someone who is melancholy, lovesick, or heartbroken – might find relief from this sweet, floral syrup.

The batch that I prepared using an updated version of this recipe was a lurid purple and had a distinct floral taste unlike the subtle orange-blossom and rosewater flavors that I usually encounter in my recipe testing.

Updated Recipe

Makes 1.5 cups syrup.

1 cup sugar

1 cup water

1 cup pansies, cleaned and tightly packed

Bring the water and sugar to a boil in a small saucepan. Stir so that all the sugar is dissolved and remove from the heat. Add the flowers. Set aside to infuse for 24 hours.

Strain the syrup through a fine strainer into a clean container. Press the flowers to capture every drop of syrup then discard the flowers.

Store in the refrigerator for up to one month.

Suggestions for using Heartsease Cordial:

Eat by the spoonful if you are lovesick.

Stir a tablespoon of the cordial into a glass of sparkling water or lemonade.

Sweeten cakes that call for a glaze or use in place of other simple syrups when making icing.

Add to any cocktail that calls for a flavorful simple syrup at your discretion.

Add to a glass of sparkling wine. (1 teaspoon or 1 tablespoon to taste.)

Make this cocktail, which is a twist on a classic Aviation cocktail:

- 2 oz gin

- ½ oz lemon juice

- ½ oz heartsease syrup

- 1 bar spoon maraschino liqueur

Measure the ingredients into a cocktail shaker with ice. Shake well. Strain into a coupe glass. Garnish with a pansy. Sip.

Further reading:

Benjamin Breen, The Age of Intoxication: Origins of the Global Drug Trade (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019) https://www.pennpress.org/9780812296624/the-age-of-intoxication/

Rebecca Bushnell, Green Desire: Imagining Early Modern English Gardens (Cornell University Press, 2003) https://www.cornellpress.cornell.edu/book/9780801441431/green-desire/#bookTabs=1

Mary Floyd-Wilson, “Potions, Passions, and Fairy Knowledge in A Midsummer Night’s Dream” in Shakespeare in Our Time, edited by Dympna Callaghan and Suzanne Gossett (Bloomsbury, 2016) https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/shakespeare-in-our-time-9781472520425/

Rebecca Laroche, Medical Authority and Englishwomen’s Herbal Texts 1550-1650 (Routledge, 2009) https://www.routledge.com/Medical-Authority-and-Englishwomens-Herbal-Texts-15501650/Laroche/p/book/9781138250529

Note of thanks: I would like to thank Rebecca Bushnell for sharing her thoughts about heartsease and Midsummer over email, Sally and Dave Falck for their hospitality, Joseph Malcomson for assistance with the cocktail recipe, and Claire Falck, Carissa M. Harris, and Thomas Ward for reading an earlier draft of this piece and sampling an array of heartsease beverages.

You must be logged in to post a comment.