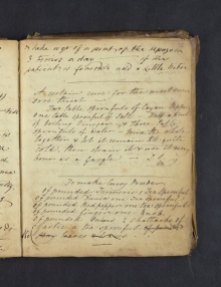

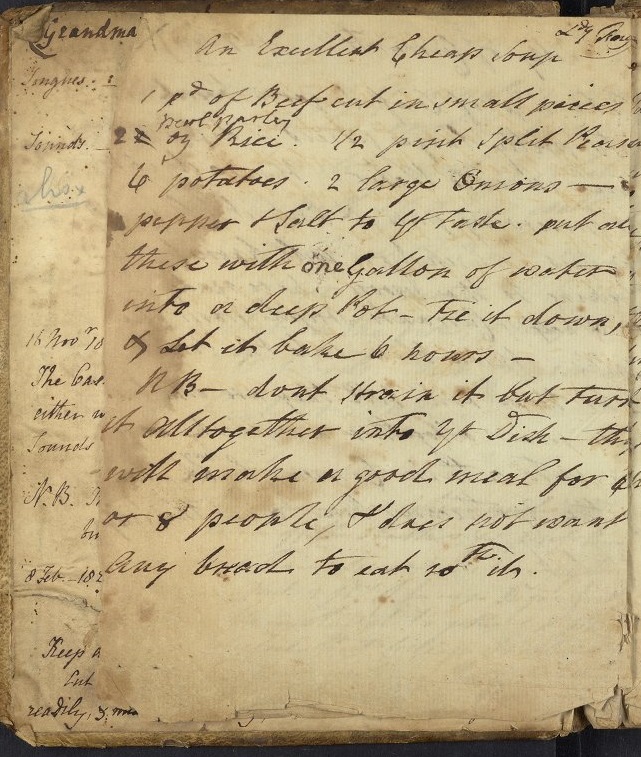

This recipe for “To make India Curry” has been on my “to cook” list for five year and I’m pleased to report that it is a subtle, satisfying, and delicious dish. Mitch Fraas brought the recipe to my attention in 2014 (!) and I’ve been cooking from and researching the manuscript, UPenn Ms. Codex 644 Grandmama Frankland’s recipe book, on and off since early 2015. But until this past spring, I was stumped by the reference to “India mixture” in the recipe. This “India Curry” was missing a crucial element: curry!

This recipe for “To make India Curry” has been on my “to cook” list for five year and I’m pleased to report that it is a subtle, satisfying, and delicious dish. Mitch Fraas brought the recipe to my attention in 2014 (!) and I’ve been cooking from and researching the manuscript, UPenn Ms. Codex 644 Grandmama Frankland’s recipe book, on and off since early 2015. But until this past spring, I was stumped by the reference to “India mixture” in the recipe. This “India Curry” was missing a crucial element: curry!

The word “curry” – “A preparation of meat, fish, fruit, or vegetables, cooked with a quantity of bruised spices and turmeric” – came into English from the Tamil word “kari” and the Kannada word “karil” that the Portugese rendered as “caril” and early modern English and French speakers called “cari” (OED). Curry powder was sold in London in the nineteenth century, but this recipe is a bit early for “India Mixture” to be sold premixed. After spending a lot more time with Ms. Codex 644, I realized that the answer had been under my nose all along. There is a Curry Powder recipe in the manuscript that I believe is meant to be used in an array of recipes in the book. It took me a good deal of looking to confirm that this recipe is in the same hand as the other recipes that call for pre-mixed curry powder of some kind. (Reader, you may also be interested in this Gastropod episode about curry that touches on the history of the powdered spice.)

Original Recipes

Cap[tai]n Pearse

To make India Curry

Cut 2 Chickens in small pieces,

wash them very clean, then let them

simmer a very little while in water

while they simmer fry a few onions

Brown in Butter: Then put the

Chickens with the water they simmerd

in into a stew pan, put to them

the fried onions, & one tea spoonfull

of the India Mixture, & a tea spoonful

of Mushroom powder: & when stew’d

enough Serve up. with a plate of

Rice boild in the following manner.

Wash & pick y[ou]r Rice very clean

Then put it into y[ou]r Sauce pan

with a very little water over a slow

fire, when the Scum rises, Skim

it clean, then cover it up close

& let it boil very slow, when t[is]

done enough turn it out in

a Bason, press out the water &

Then Turn the Bason over a Dish

& let it come up in the shape of

the Bason.

To make Curry Powder

Of pounded Turmeric 1 Tea spoonful

Of pounded Dunia one Tea spoonful

Of pounded Red pepper one tea spoonful

Of pounded Ginger one knob

Of pounded Onions 2 chattachs of

Garlic a tea spoonful of pounded

No ( Bay leaves 2 leaves

The curry powder is more of a curry paste since it includes fresh onion and garlic. In my updated version, I used fresh ginger and powdered turmeric because that’s what I had to hand, but I’d love to hear from anyone who tries fresh turmeric here. Dunia is an English transliteration of the Hindi word for coriander. I’ve also used ghee – butter with the solids removed – to sear the chicken before boiling as the original recipe instructs. Ghee is a traditional ingredient in Indian cuisine and I had some to hand. I did not try the trick for molding the rice into a dome because it was pretty crazy in my kitchen already, but I’d love to see results if you do! Finally, I used a whole chicken here because that’s what I tend to buy and, of course, what the original recipe calls for. You could also use a mix of chicken thighs, legs, and boneless breasts. I’ve included instructions for making chicken stock as well as stock comes in handy for this recipe and so many others.

Updated Recipes

Curry Paste

1T powdered turmeric

1T coriander seed

1 T red chili pepper flakes

1 2-inch knob ginger, peeled

1 small onion

2 garlic cloves

Chop the ginger, onion, and garlic into small pieces. Either blitz in a food processor or bound with a mortar and pestle until a (somewhat) smooth paste forms. (I mixed my batch by hand and there were still some visible pieces of onion.)

Store in a jar in the refrigerator. Use within a month.

Chicken Curry

(Serves 4 if accompanied by rice and cooked greens)

1 chicken, fresh or defrosted (or equivalent, mixed precut chicken)

1T ghee (or neutral cooking oil)

2 onions

2T butter

1T curry paste

1/2 cup mushroom broth (made from mushroom powder or dried mushrooms)

1t salt

Cut up the chicken so you have two leg/thigh pieces, two breasts, and two wing pieces. Slice two onions.

(Optional: Put the chicken carcass, any innards that may have come with the chicken, and the tops of your onions in a stock pot. Bring to a boil and then cover and simmer while you make the curry. You can use this very flavorful stock in place of chicken cooking water later in the recipe and you can even use this stock to make your mushroom broth. Alternatively, you can make a batch of chicken soup or fill your freezer with about a gallon of stock.)

Heat ghee or neutral cooking oil in a large skillet or frying pan. Sear the chicken on both sides, 1 minute per side. Depending on the size of your chicken, you may need to do this in batches.

Heat 2T butter in the same pan and cook the onions on a medium heat for 15 minutes until brown and soft. While the onions are cooking, put the seared chicken pieces in a large pot, cover with water, and bring to a boil. Then turn the temperature down, cover, and simmer for 15 minutes. Prepare your mushroom broth while the chicken and onions are cooking.

Remove the chicken from the water, reserve the cooking water, and place the chicken pieces in the skillet with the onions. Add the curry paste by coating one side of the chicken pieces with it. Sprinkle the salt over the chicken. Pour in the mushroom broth and two cups of the chicken cooking water (or optional stock from your stockpot). Simmer for 5 minutes, flip the chicken pieces, and simmer for 5 more minutes (or until the chicken is fully cooked).

Serve with cooked rice and greens for a full meal.

The Results

Since the curry paste is added so late in the cooking process, the flavor is mild and floral. When I ate the curry for lunch it was tasty: When I served it to my spouse Joseph for dinner with a side of cooked mustard greens it was even better. Later in the week, the flavors were even more potent, but still floral. This is a great dish to make ahead.

I’d like to thank Joseph Malcomson for taste-testing and helping me figure out if the recipe called for dunia or mentioned a merchant (bunia).

You must be logged in to post a comment.