I’ll be speaking about this recipe (and more) at a free, public, virtual event hosted by The Free Library of Philadelphia on Tuesday December 8th, 7pm EST. Register here: https://www.eventbrite.com/e/medieval-life-spotlight-cooking-digital-demonstration-tickets-130045243825

Medieval and Renaissance European cooking was heavily spiced. Until fashions changed in the eighteenth century, wealthy and aspirational households used spices imported from Asia in all sorts of sweet and savory dishes. Cooks flavored dishes with black pepper, long pepper, nutmeg, mace, cinnamon, cassia, ginger, galangal, and the spice that flavors this recipe, cloves.

Over the past few months, I’ve been discussing cloves, historical recipes, and how the high price of spices motivated European colonial and imperial ventures with Chef Ange Branca (Sate Kampar). Next week, we’ll be speaking at this free, public, virtual event hosted by the Free Library of Philadelphia in connection with the exhibition “Medieval Life” curated by Dot Porter (UPenn Libraries). Unsurprisingly, our conversations had me reading, looking at recipe books, and cooking.

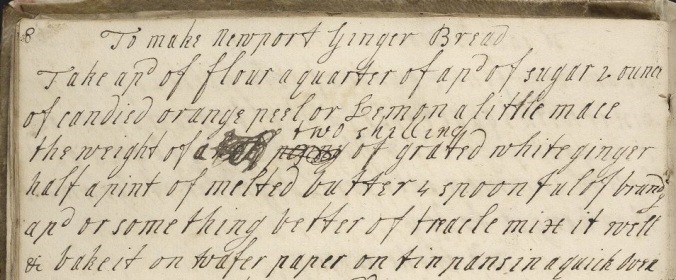

This recipe for “Instructiones to make Cakes” is from a sixteenth-century English manuscript, UPenn Ms. Codex 823 (22v). The “cakes” made from flour, butter, sugar, and cloves are more like a shortbread cookie than fluffy modern cake. Fragrant with cloves and crumbly, these are delicious cookies are wonderful hot from the oven with a cup of coffee or tea.

Cloves were especially prized in medieval and Renaissance kitchens because of their unique floral flavor. In his wide-ranging discussion of cloves, among other imported spices, in Out of the East: Spices and the Medieval Imagination, Paul Freedman shows that scholars wrote about the origin of clove trees in the garden of Eden, that cloves were purchased in huge quantities for use in medicines and cookery, and that Portuguese ships were specifically sent to target the clove island of Ternate in 1513 (205). Freedman quotes Tomé Piers, a pharmacist and diplomat, who wrote “Whoever holds Malacca has his hand on the throat of Venice” and, consequently, control of the global spice trade (205). While Freedman notes that the Venetian spice trade survived the Portuguese conquest of Malacca, European desire for spices nevertheless drove colonial ventures.

This recipe calls for “iid cloves” (2 d, or 2 pennies, worth of cloves) and thus demonstrates the connection between the price and measurement of spices. Working with Freedman’s book and John Munro’s account of spice prices, I believe the original recipe calls for 6 whole cloves that would have cost 2 pence. For comparison, in the sixteenth century a loaf of bread cost a penny and bread provided far more sustenance than a few cloves. In my updated recipe below, I’ve quartered the recipe from the original and used the equivalent of 1.5 cloves to flavor about a dozen cookies. Even though the original recipe calls for expensive cloves, it uses them sparingly and in balance with the other flavors and ingredients. The sugar in these cookies (which I’ve written about elsewhere), would also have been imported and far more expensive than the flour and butter called for in the recipe. A little bit of clove goes a long way, as anyone who has prepared modern recipes with them knows well.

Ms. Codex 823 was created and used from approximately 1567-1600 and unlike many of the manuscripts that I’ve featured on this site, it is not primarily filled with recipes. More of a commonplace book than a recipe book, this manuscript includes pages of Psalms copied from a Bible or prayer book and a copy of the deathbed statement of Lady Katherine Grey before the final section of medicinal and culinary recipes begins. Although the manuscript is miscellaneous, the recipe section is a familiar blend of medicinal and culinary preparations with a focus on preserving fresh foods. The page above includes the recipe for “cakes” and well as recipes to make vinegar, preserve pears and barberries, and prepare “white pott,” which in this version is rather similar to bread pudding.

Ms. Codex 823 was created and used from approximately 1567-1600 and unlike many of the manuscripts that I’ve featured on this site, it is not primarily filled with recipes. More of a commonplace book than a recipe book, this manuscript includes pages of Psalms copied from a Bible or prayer book and a copy of the deathbed statement of Lady Katherine Grey before the final section of medicinal and culinary recipes begins. Although the manuscript is miscellaneous, the recipe section is a familiar blend of medicinal and culinary preparations with a focus on preserving fresh foods. The page above includes the recipe for “cakes” and well as recipes to make vinegar, preserve pears and barberries, and prepare “white pott,” which in this version is rather similar to bread pudding.

The Recipe

Instructiones to make

Cakes

Ffyrst take a quarte of fyne flower a pound of Sugar iid of

Cloves fyne beaten and thereunto put a pound of swete butter & then

worke yt together untyll suche tyme as you shall thincke yt

well wrought & so make yt in cakes & put yt in to the oven

wher manchete or cakes hathe bene baked imedyatelye after the

same ys drawen – And you myt note that to the baking of fyne

cakes a temperate heate myt be in the oven & you myt not

suffer them to stande in the oven tyll they be browne because

they mytt harden and wax browne when they be browne after they have

stand a whyle

Updated Recipe

makes a dozen cookies

½ cup sugar

8 Tablespoons butter (1 stick), room temperature

1 cup flour

1/8 teaspoon ground cloves

Additional butter or baking spray for the pans

Preheat your oven to 275F. Prepare a baking sheet with baking spray or butter.

Cream together butter and sugar until pale and fluffy.

Add the flour and cloves to the butter mixture to form a workable dough. It will be crumbly, but will hold together when pressed. The finished texture is like a shortbread cookie and do not worry if your cookies only barely hold together.

Put the cookie dough onto a cutting board. You can either shape the dough into a log with your hands and slice cookies from the log or shape the dough into small cookies by hand. Place the formed cookies on your prepared baking sheet.

Bake for 30-35 minutes until just firm, but still tender.

Allow to cool for a few minutes on the pan. Serve slightly warm or completely cooled.

You must be logged in to post a comment.