These preserved quinces, like the preserved apples and apricots, will be a delightful accompaniment to the pancake recipes we posted last week.

When I was in kindergarten, our class held an alphabet feast. Each of us was assigned a letter of the alphabet and tasked with providing a food whose name began with that letter. The “A” student could bring apples, the “P” student could bring pie, as the “Q” student I faced a great challenge. But, as always, my brilliant and resourceful mother had an idea: Quince Jam. I’m not sure I had ever tasted quinces before that day when we finally found a jar of imported Quince Jam after visiting what seemed like every specialty store in the western towns of Essex County, NJ. The “Q” student in the the other class may have had an easier time making quiche than hunting for quinces, but I think that my mom and I came out on top. My classmates and I ate quince jam on saltines sitting cross-legged on the classroom floor, or at least that’s how I remember it. I don’t think I tasted quince again until the man who is now my husband poached them in wine for dessert one cold winter evening in London.

Recalcitrant and inedible in their raw state, quinces have long inspired fear and love among cooks. Amanda E. Herbert shows how a gifts of “Marmalade of Quinces,” or other sugared fruits, circulated in a female social network in her book Female Alliances: Gender, Identity, and Friendship in Early Modern England. Local, hearty English quinces were softened and tempered with boiling and the extravagant use of imported sugar. Preserved quinces shared between women demonstrated generous consumption of expensive sweeteners and inborn feminine skills at taming the unruly quince. Molly Wizenberg’s recent post on Orangette reflects a twenty-first-century view of this very same issue and offers a great, simple recipe for taming and tenderizing this “esoteric fruit.” Since that early encounter and more recent reintroduction, I’m hooked on quinces. I’ve been making Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall’s Sticky Quince and Ginger Cake for years now, Nigella Lawson’s Quince Meat is my household’s standard mince pie filling (or at least it was before these came along), and I’ve long admired quince-whisperer Nigel Slater’s recipes.

This recipe from UPenn MS Codex 252 instructs cooks in a complex method for preserving quinces in a gelatinous liquid thickened with sugar and pectin from apples and the quinces themselves. Our recipe, below, is a bit simpler.

The Recipe

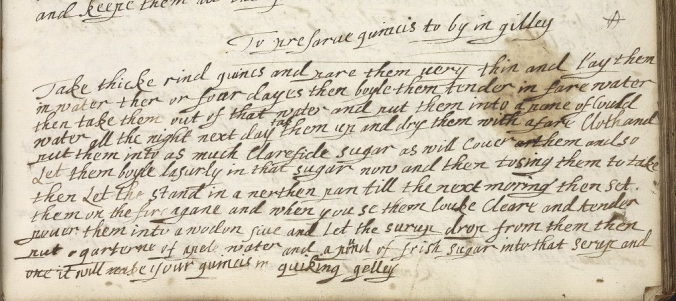

To presarue quincis to by in gilley X

Take thicke rind quincs and pare them uery thin and lay them

in water ther or four dayes then boyle them tender in fare water

then take them out of that water and put them into a pane of could

water all the night next day tak them up and dry them with a fare cloth and

put them into as much clarefide sugar as will couer or them and so

Let them boyle lasurly in that sugar now and then tosng them to take

then Let the stand in a nerthen pan till the next moring then set

them on the fire agane and when you se them louke cleare and tender

pouer them into a woden sive and let the surup drop from them then

put a quarterne of apele water and a pound of frish sugar into that serup and

one it will make your quincis in quiking gelley

Despite the lengthy description of cooking methods in this recipe, it is easy to streamline and requires very few ingredients. A quick search on Early English Books Online reveals many uses of “apple water,” or water in which apples have been boiled, in culinary and medicinal recipes. For this recipe, it seems to add pectin to the preserving liquid.

Our Recipe

1 quince

1 apple

3/4 c sugar (to use in 1/4 c and 1/2 c quantities)

6 c water (to use in 2 c quantities)

1 jar (if you plan to can these or prefer to store them in a jar)

*These proportions yield 1 ball jar of stewed quinces in sweet liquid. This can easily be doubled or tripled to preserve more fruit.*

Peel and core a quince. Slice it thin. Soak in two cups of cold water overnight (or for a few hours depending on what suits your schedule).

Drain the quince from the soaking water and put in a pot with 1/4 c sugar and 2 c water. Bring to a boil and then turn it down to a simmer to cook the quince “leisurely” until soft. (I let my quince simmer for about two hours while I was doing other things.) Using a colander, strain out the quinces and discard the cooking liquid. Set quinces aside.

Either during the last half hour of cooking the quinces, or after, prepare a jar and make the apple water/preserving liquid.

Fill your jar with boiling water and then discard. Put the quinces in the jar.

Roughly chop an apple, skin core and all. Put the apple in 2 c water in a pot. Bring to a boil and then simmer for a half hour. Remove the apples and add 1/2 c sugar to the cooking liquid. Boil until the sugar dissolves. Pour this liquid into the jar with the quinces. Let cool before covering.

The Results

Now, these preserved quinces did not last long in my kitchen. (I eating them with pancake, ice cream, yogurt, cake, etc.) I cleaned my jar with boiling water, but I did not properly can these. If you want to can a batch of these, Marisa McClellan has great advice over here on Food and Jars and in her cookbooks.

Unfortunately, the syrup did not become jelly. I think this is partly because the original recipe instructs cooks to discard the pectin rich quince cooking water. On the other hand, perhaps my apple water could have been prepared more effectively. Luckily, the non-jellied liquid made an awesome syrup for the pancakes. Let us know if your quinces jelly!

I really enjoy to follow your “Manuscrit” Recipes 🙂

carnetderecettesduweb.wordpress.com

Perhaps they didn’t set because you didn’t follow the instructions.

“let the surup drop from them then put a quarterne of apele water and a pound of frish sugar into that serup”

You don’t “discard the pectin rich quince cooking water”, you use it. I do love this blog, but this is the second time you have complained about the outcome because you didn’t properly translate the recipe. 😦

Hi Carson,

Take a look again. The original recipe calls for you to discard the first batch of water that the quinces are cooked in. I think that this water would be the most rich in pectin.

Let us know if you try the recipe and it works out for you!

M

I believe the problem with this recipe is that you are directed to peel the quinces, and just like apples, the peel is where the pectin lies. My go-to lady for 18th century directions that work is Hannah Glasse. This is her receipt for Quince Jelly: “Take some of the lesser Quinces and wipe them with a clean coarse Cloth; cut them in Quarters, and put as much Water as will cover them, let them boil apace, till it is strong of the Quinces, then strain it thro’ a Jelly-bag; if it be for white Quince pick out the Seeds, but none of the core nor Quinces pared.” She has you making up for the discarded peels and their pectin by adding apple water, but it is apparently not sufficiently strong to jell your liquid. I’ve done it and it works just fine.

Mercy Ingraham

Pingback: To Make Quince Cream | Cooking in the Archives