This post presents the third recipe from a series of updated recipes that I developed for the Folger Shakespeare Library exhibition, First Chefs: Fame and Foodways from Britain to the Americas (on view Jan 19–Mar 31, 2019). You can also find a version of this post on the Folger’s Shakespeare and Beyond blog.

Photo by Teresa Wood

Citrus and sugar: What could be more precious than marmalade?Oranges and other citrus cultivars come from the mountainous parts of southern China and northeast India. They were prized for their beauty, scent, and medicinal properties in this region long before Europeans saw, smelled, or tasted an orange. As Clarissa Hyman writes in Oranges: A Global History, “In India, a medical treatise c. AD 100 was the first to mention the fruit by a term we recognize today. Naranga or narangi derives from the Sanskrit, originally meaning ‘perfumed from within’” (10). The three original citrus cultivars were the citron (prized for its thick, fragrant peel), the pomelo, and sour oranges, called China or Seville oranges in early modern England. Easily hybridized, these three cultivars are the origin of all modern citrus varieties. Soldiers returning from the Crusades brought citrons and sour oranges home with them. In the early modern period, sweet oranges, sour oranges, lemons, citrons, and exotic varieties like bergamot and blood orange were widely cultivated in Southern Europe and by wealthy gardeners who build special hot houses, or orangeries, further north.

Photo by Teresa Wood

Shakespeare provocatively references oranges in his often troubling comedy Much Ado About Nothing. Claudio is misled by Don John into believing that his betrothed, Hero, has been unfaithful. In a fit of anger, he sends her back to her father calling her a rotten orange: “There, Leonato, take her back again. / Give not this rotten orange to your friend” (IV.i.29-30). Earlier in the play, witty Beatrice likens Claudio himself to an orange in lines that foreshadow Claudio’s jealous rage. She calls him “civil as an orange, and something of that jealous complexion” because, like the “Seville” orange referenced in her pun on “civil” he can be sweet or sour, loving or jealous (II.i.287).

Photo by Teresa Wood

In 1493, on his second voyage to the Americas, Christopher Columbus brought bitter oranges to Haiti (Hyman 19). Oranges thrived in the Caribbean, and by the late seventeenth century, the time when Hannah Woolley was rising to prominence as a Restoration lifestyle guru, American oranges were being shipped to Britain. This influx of oranges reduced their price and made oranges accessible to a larger portion of the population. Nell Gwynn sold oranges and sweets to theater-goers before she became an actress, and before she became the mistress of King Charles II. Naval bureaucrat and diarist Samuel Pepys writes about buying a whole box of China oranges on 16 February 1659/60. The popular London tune has the bells of St. Clement ringing out “oranges and lemons” when ships laden with citrus docked in the harbor (Hyman 90-1).

Woolley’s marmalade captures the flavors of exotic citrus while it’s fresh, and she can only do so through the preservative power of sugar–now also widely available to upper- and middle-class British people for the first time. Kim Hall’s work on sugar and status in the early modern era rightfully insists that women’s aspirational confectionary work deeply implicated them in the labor conditions of enslaved people of African and Caribbean descent who worked in orange groves and sugar cane fields halfway around the world. It is only these global systems of exploitative labor and overseas shipping that would allow an accomplished lady to prepare a citrus marmalade.

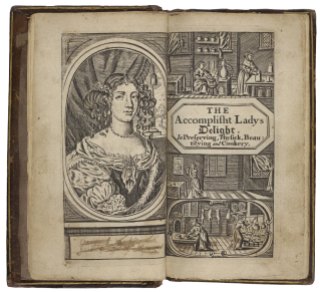

The accomplisht ladies delight is a work which took advantage of Hannah Woolley’s fame and popularity. This book was published in 1684 after Woolley’s death and capitalized on the success of Woolley’s Queen-like closet, first published in 1670 to great fanfare. However, the book’s recipe for marmalade is rather similar to marmalade recipes in The Queen-like Closet, a work that we can confidently attribute to Woolley.

To make Marmalade of Lemmons and Oranges. You may boyl eight or nine Lemons or Oranges, with 4 or 5 Pippins, and draw them through a strainer; then take the weight of the pulp altogether in Sugar and boyl it as you do Marmelade of Quinces, and so box it up. (A9r)

Boil citrus to soften it; boil pippins (or apples) to add pectin, sweeten and preserve using sugar; store carefully. Making marmalade takes time and attention. Now, at least we can use a candy thermometer to determine when the mixture has hit an ideal temperature instead of only watching the sugar change color and texture. A crucial “plate test”—seeing if preserves stay solid on a cold plate—was part of Woolley’s marmalade recipe in The Queen-like Closet,and it’s an important step in my recipe as well. Spread your marmalade on hot toast or a warm baked good and enjoy.

INGREDIENTS

1 orange

1 lemon

1 apple

Sugar (3+ cups)

Water (4+ cups)

EQUIPMENT

Baking scale

Candy thermometer

PREPARATION

Weigh the fruit on a scale. Measure out an equal weight of sugar. If less than a pound of fruit, use 4 cups of water. If more than a pound of fruit, increase to 5 cups of water. Cut the citrus into slices 1⁄8 inch thick and then quarter them. Peel, core, and cut the apple into thin slices. Put the fruit and water into a 3 quart saucepan. Cover and bring to a boil. Lower to a simmer for 40 minutes. Put a small plate in your freezer. After 40 minutes, gently stir the fruit. The apple slices will be soft and should break down when touched. The citrus fruits will have softened. Place your candy thermometer in the pot. Add the sugar, stirring constantly as the fruit breaks down, the mixture thickens, and the marmalade takes on a light caramel color. Cook until the temperature reaches 240°F (soft ball stage or candy height). As your marmalade nears temperature, put 1 teaspoon on the freezer plate and let sit for 30 seconds. If the marmalade holds its shape when you tilt the plate, it has set. If the marmalade is browning quickly or looks set before the temperature reaches 240°F, try the plate test earlier. Put your set marmalade in a clean pint jar.

NOTES

Serve the marmalade with bread, scones, muffins, or biscuits. Store this small-batch preserve in the refrigerator and consume within two weeks. You can extend the life of your marmalade by properly canning it or by freezing it. You can make more marmalade by increasing the amount of fruit and adjusting the sugar and water and cooking times accordingly.

Learn More

Hall, Kim F. “Culinary Spaces, Colonial Spaces: The Gendering of Sugar in the Seventeenth Century,” in Feminist Readings of Early Modern Culture: Emerging Subjects, eds. Valerie Traub, Lindsay Kaplan, and Dympna Callaghan (Cambridge University Press, 1996), 168-90.

Hall, Kim F.“Sugar and Status in Shakespeare” Shakespeare Jahrbuch145 (2009): 49-61.

Hyman, Clarissa. Oranges: A Global History (London: Reaktion Books, 2013).

Mintz, Sidney W. Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. New York: Penguin, 1986.

This recipe was developed by Marissa Nicosia for the Folger exhibition, First Chefs: Fame and Foodways from Britain to the Americas (on view Jan 19–Mar 31, 2019), produced in association with Before ‘Farm to Table’: Early Modern Foodways and Cultures, a Mellon initiative in collaborative research at the Folger Institute.

Special thanks to Amanda Herbert and Heather Wolfe for their help.

I see one major issue with your interpretation of this recipe: in 1675, “pippin” referred to seeds, or pips. (Check your OED.)The pippin variety of apple didn’t exist in England at that time.

The seeds of the citrus were removed from the fruit either before or after the first boil, and placed in a cloth bag to make them easier to retrieve. With most modern fruit, the extra pectin supplied a 4 or 5 seeds is trivial. It may have been different in the past. The boiling of the citrus in water also served to “sterilize” the fruit, even though 17th-century cooks had no concept of sterilization. It would wash any settled dirt from the fruit. Today, the boil is unnecessary.

Very good marmalade can be made from sliced, modern fruit cooked raw in an equal weight of sugar over low heat. When the bubbles are small and tight, the cooking is done. No additional water is needed at the start of cooking.

Thank you for this interesting set of observations on my recipe. I do have to correct you on the use of pippins. Perhaps the original recipe was referring to seeds, but it could have also been referring to apples. As the OED definition 3.a. explains “Pippin” referred to kinds of apples in English as early as 1435: “ 3. a. Formerly: a kind of sweet apple, typically late-ripening, fine-flavoured, and having good keeping qualities. Now (frequently with distinguishing word): any of numerous fine-flavoured varieties of dessert apple.

Blenheim, fall-, golden-, Newark, Newtown, orange, Sturmer pippin, etc.: see the first element.”

Nonetheless, I’ve not seen other recipes of the period where apple flesh was combined with the citrus. There are references to using “Jelly of Pippins” as a gelling agent. The pectin in apples is mostly in the skin and seeds so using the flesh doesn’t make sense. Have you found any other recipes from the period that use apple flesh?

There’s a lot out there! This recipe, from the same volume (The Accomplisht Ladies Delight), instructs you to core the apples, cook the flesh, and use the juice in the marmalade.

265. To make Marmelade of Oranges.

After you have pared your Oranges very thin, let them be boyled in three of four waters even till they grow very tender, then take a quarter of a hundred of good Kentish Pippins, divide them, and take out the Cores, boyl them very well to pap or more, but let them not lose their colour, then pass your Apples through a strainer, and put a pound of Sugar to every pint of juice, then boyl it till it will Candy, then take out the pulp of the Orange and cut the peel into long slices very thin, put in your peel again, adding to it the juyce of two or three Lemons, and boyl it up to a Candy.

Ultimately, I think these recipes make a very different marmalade than we might make today with texture being the main difference.

Apologies for my delayed response. I was traveling and away from my notes.

Pingback: Emily’s Journey Through the Boyle Family’s Recipes – Emily’s Journey with the Boyle Family’s Recipes

Hi Marissa: My “Writing, Making and Knowing” class has just read Hugh Plat’s _Delights for Ladies_ and the exact same recipe (in section one, number 41) with the same wording appears there, so it’s clear where Woolley got this recipe. I am curious about the discussion above, as I was also thinking about pippins as apples, but I did see another recipe from Jane Staveley,, Folger MS 401, page 38, which uses the pips or seeds as the thickening agent. This recipe is a multi-day one, so I don’t know if I will try it. Anyway, we are making marmalade next week, so I am thinking about trying the same recipe (from Plat) with the pips only. I’ll let you know what happens.

Cheers, Amy

Just another note about the discussion above concerning the thickening agent as either pips or pippins: I have been looking at Ann Fanshawe’s recipe for “To Make Marmalade of Oranges” (Wellcome MS 7113, p. 382), and it uses apple water as a thickening agent. Later in the manuscript, there is a recipe for “To Make a Jelly of Apple Johns to lay on Oranges,” (p. 385) which is what I think she is using in the Marmalade recipe. Also, there is also a “Jelly of Pippins) on page 379, which is clearly an apple jelly. So, I’m inclined to believe that Woolley and before her Plat really did mean to use pippins not pips as the thickening agent, especially as the recipe specifies the number of pippins. If you had 4 or 5 pips or seeds, the thickening they would provide would be negligible; whereas 4 or 5 pippins would provide quite a bit of pectin. Cheers!

Amy, thank you for these comments! It’s helping me place Woolley, her imitators, Staveley, Fanshawe, and Plat in a dialogue about marmalade method. I think these examples do show that the flesh of pippins was crucial for the thickness of these preserves, whether pulp or pectin made the contribution.

Pingback: Meringues – To Make Lemmon (or Chocolett) Puffs | Cooking in the Archives

This is a lovely recipe and an interesting discussion. My offering would be to point out the HUGE difference between the taste of sweet naval oranges, and the taste of a Seville Orange;. VERY different. I have had some success in finding them in high end grocery stores in January for up to $2 each. If you can’t find them we add some lemon to move it toward the tart taste profile, but you really want a Seville Orange to do it justice. I have a friend in Florida who says they are being grown there. And I believe they are the reason that British Marmalade tastes so much better than ours.

Thank you so much for this, Mercy. I absolutely agree. That’s one of the reasons that I have the lemon in this recipe.

Out of curiosity, why did you select to adapt the recipe from “The Accomplish’d Ladies Delight” rather than “The Queen-Like Closet”? Thanks for sharing, this is fascinating and was a wonderful quarantine project!

Thank you!

I was working with the curators of the Folger exhibition as I selected recipes and they were interested in how to pair the two books – one by Woolley and one by an imitator – in the display. I liked the simplicity of the recipe from “The Accomplish’d Ladies Delight” and decided that it would contribute to the story that the exhibition was telling about Woolley’s fame.

Pingback: To preserve Strawberries | Cooking in the Archives