We wrote a version of this post over on The Recipes Project.

Rice pudding is simple. Neutral in color and mild in taste, rice pudding has a minimal list of ingredients and always pleases a crowd. It’s also familiar – most of us have encountered rice pudding at one time or another. So, when we kept seeing lists of rice pudding recipes in manuscript recipe books from many centuries, we wondered: why rice pudding? And what, if any, differences were there between past and present versions? So, we decided to make not one but two distinct rice pudding recipes. A rice pudding face-off!

While in the twenty-first century the ingredients required to make rice pudding are pantry staples – rice and sugar are readily available, as is dairy – in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century English households, rice pudding was probably a more exotic affair. After all, England does not produce any of its own rice. We asked another question: where did this rice come from?

This sent us on a hunt for early modern England’s rice suppliers. Today, as in the past, the majority of the world’s rice is produced in Asia. Until the later decades of the seventeenth century, England’s rice came from Asia through overland routes or through overseas trade. (For more information, see Renee Marton’s Rice: A Global History and Rice: Global Networks and New Histories, ed. Francesca Bray et al.) The rice that made its way into England’s kitchens in the later seventeenth and eighteenth centuries would likely have come from British colonies in South Carolina. Carolina Gold Rice was developed from African seed stock and is distinct from Asian varieties.* It thrived in the Low Country, anchored South Carolina’s economy, and was largely cultivated by African slaves. Scholars of American history and food are currently debating the theory of “Black Rice,” first proposed by Judith Carney, which argues for the centrality of West African women’s agricultural knowledge to the successful cultivation of rice in the Carolinas. *[Correction: Naomi Duguid pointed out that Carolina Gold Rice is neither from Africa nor indigenous to the Americas. It most likely arrived on a ship from Madagascar or the East Indies. See her book, The Seductions of Rice, on this topic.]

Chefs and food writers often refer to this meeting of cultures, climates, and ingredients as the Carolina Rice Kitchen. Rice was the foundation of a local cuisine and an important export. Non-aromatic but nutty, Carolina Gold Rice was world-renowned. The PBS show Mind of a Chef included this animated history of Carolina Rice in an episode where Chef Sean Brock makes a passionate case for recovering lost food traditions. For more information about Carolina Gold Rice and southern heritage foods, take a look at these resources: Carolina Gold Rice Foundation, the Southern Foodways Alliance, Anson Mills, and food historian David Shields’ new book, Southern Provisions. The recipes we decided to cook for this rice pudding-off were both included in manuscripts from a particular historical moment: the moment when the rice supply-chain changed and Carolina Gold Rice arrived in England’s kitchens.

Our rice puddings come from LJS 165 and MS Codex 631. Each recipe is just one in a cluster of rice pudding recipes, demonstrating cooks’ variations on a base recipe that we’ve seen with other dishes like jumballs and syllabubs. (Rice pudding could also be turned into other recipes: two rice pudding recipes in MS Codex 631 include instructions for adapting them to almond puddings instead.) For contrast, we chose to cook one recipe that started with whole rice and another that used rice flour as a base.

Indeed, we were intrigued, even surprised, to see rice flour in an eighteenth-century recipe. More and more modern cookbooks are exploring a wide range of flours, but what was the place of rice flour in early modern cooking? Rice flour (often “rice flower” or “flowre”) was used as a thickening agent in a range of early modern dishes. Seventeenth-century print cookbooks like The Compleat English and French Cook (1690) and Joseph Cooper’s The Art of Cookery (1654) both call for rice flour in “Cream with Snow” (sweetened cream thickened with rice flour and eggs, then topped with more cream). They also use rice flour in Almond Cream and Rice Cream, as does The Compleat Cook (1694), which also provides a recipe for “Custard without Eggs” using rice flour. The Gentlewomans Cabinet Unlocked (1675) tells how to make Rice Milk. Other rice flour puddings can be found; some add chopped dates and/or currants to the mixture, while others top the pudding with a pastry crust. The use of rice flour as a thickening agent continued well into the eighteenth century: print cookbooks like A Collection of above Three Hundred Receipts in Cookery, Physick and Surgery (1714), The Court and Country Confectioner (1770), and Amelia Chambers’ The Ladies Best Companion (1775?) often use rice flour in cheesecakes and in the filling for chocolate tarts.

The Recipes

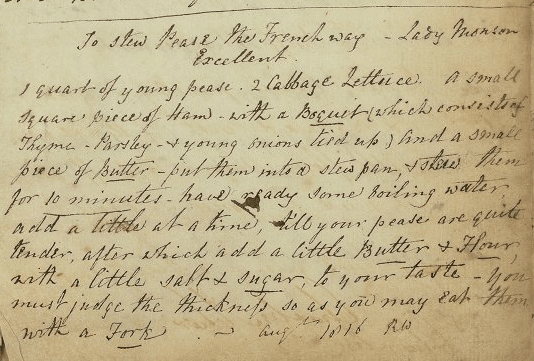

A whole grain rice pudding from LJS 165.

Rice Puding

A quart of Creame a pound of Rice 2 Eggs, Orangado a

1/4 of a pound, Cinamon a quarter of a pound an Ounce, a

little Rosewater & Ambergreese some grated bread 3/4 of a

pound of suger some Marrow boyle Salt in the Creame

Apparently it is still trendy to flavor rice pudding with cinnamon and orange because a quick search turned up this Food Network recipe. I made two small changes to this recipe: I halved it (and it still made a huge amount) and I didn’t add aromatic ambergris and bone marrow to the mixture. In retrospect, I also wonder if a combination of milk and cream might work better here than cream and the water I added to stop the rice from sticking. After all the talk about Carolina Gold Rice, I’m almost ashamed to admit that I tried this recipe with Jasmine Rice instead. It’s what I had to hand and it worked, although I’m sure Carolina Gold Rice would add a distinctly nutty flavor to the pudding.

2 cups heavy cream

2 cups water

3/4 cup sugar (3/8 lb. or 165 g.)

1/2 tsp. cinnamon

1/2 tsp. rosewater

1/4 tsp. salt

3-4 strips of orange peel

1 cup and 2 tbsp. rice (1/2 lb. or 225 g.), preferably Carolina Gold Rice

1 egg

1 small piece of bread, grated. Or 2 tbsp. bread crumbs.

Heat the cream, sugar, and seasonings: cinnamon, orange peel, and rosewater.

Add the rice and bring to a boil. Cover and cook for 45 min-1 hour until the rice is tender. Stir frequently (every 5-10 minutes) to keep the rice from sticking. Add additional water if the liquid is very low and the rice is still hard.

When the rice is cooked, stir in the egg and bread. Cook for 5 more minutes.

rice pudding (whole grain)

rice pudding (whole grain)

rice pudding (whole grain)

rice pudding (whole grain)

rice pudding (whole grain)

Rice flour puddings from MS Codex 631.

To Make a Rice Pudding

Take six ounces of Rice flower a quart of milk set them over [th]e fire & stir them well

together while they are thick, then put in half a pound of Butter six eggs one nutmeg sweeten

it to y[ou]r tast, Buter y[ou]r Dish that you Bake it in /

I halved this and used ground nutmeg because that’s what I had; otherwise, I followed the original recipe closely.

3 oz. rice flour (~1/2 c.)

2 c. milk

1 stick butter, diced

3 eggs

1/2 tsp. nutmeg

1 tbsp. sugar

Preheat the oven to 350F and butter/spray a 9″ pie dish or similar baking dish. Combine the rice flour and milk in a saucepan; cook over low-med. heat, whisking frequently. The mixture will thicken quite suddenly, so be attentive! Off the heat, stir in the butter, eggs, nutmeg, and sugar. Bake for 40 mins., until top is puffed and golden brown. Let cool on a wire rack and serve warm or at room temp.

The Results

Our rice pudding-off was a success! These rice pudding couldn’t look or taste more different. The “whole grain” rice pudding from LJS 165 is toothsome, with surprising depth of flavor from the caramelized sugar and rosewater. The cinnamon adds a spicy note, but the orange flavor is harder to identify. We might switch out the rosewater for orange flower water next time. (If you are not a fan of rosewater, you can probably leave it out altogether.) This rice pudding is especially thick. Even before we added the egg and the grated bread the mixture was already dense. The eggs and bread may have been intended to add bulk to the dish, as rice was certainly more expensive than stale bread!

The rice flour pudding, on the other hand, is fairly bland. Nutmeg is the primary seasoning; even the strong notes of nutmeg don’t cut just how creamy this pudding tastes. (Note: some more sugar or some honey might be welcome. However, this doesn’t seem meant to be overly sweet, unlike the whole grain version.) It reminded us of buttermilk pie and South African milk tart, with an even firmer baked texture. It would form a good base for other tastes: served with fresh or stewed fruit, for instance, or with additional flavors added to the pudding.

In the eighteenth century, rice pudding represented the world in a bowl. Rice from West African seeds was cultivated in American soil by enslaved Africans in the Carolinas and shipped east across the Atlantic to England. The sugar probably came from the Caribbean. Nutmeg and cinnamon from places like the Moluccas made their way west through Asian and European ports. Oranges imported from Seville and other warmer climates scented the dish. The eggs, milk, cream, and bread are the only ingredients early modern cooks would have been able to source locally. These ingredients rely on both trade and labor – their production depended on plantation agriculture and their presence in England came from a highly developed global transport network. It’s not as if these structures don’t underpin many – if not all – of the recipes we’ve cooked so far. However, paying particular attention to this single ingredient, rice, has challenged us to consider how ingredients entered early modern kitchens in the first place, even before they became the recipes in a household manuscript.

What surprised us most about making these dueling rice puddings was not the questions of culinary and economic history they raised up, but the true difference in taste. In both, the taste of the rice remains – even through the single note of nutmeg in the rice flour pudding and the dense combination of flavors in the rice grain pudding. The taste difference, furthermore, is deliberate: the presence of multiple rice pudding recipes – similar but distinct – within the same manuscript recipe book indicates attempts to explore the versatility of this ingredient, to incorporate other flavors into a recipe that has one umbrella name but many flavorings and techniques. We’d be curious to taste these again using heritage rices, direct descendants of the Carolina Gold Rice these cooks and their contemporaries would most likely have used. In both cases, we were able to follow the ingredients and techniques fairly closely (minus ambergris and marrow), so what we tasted in our dueling rice puddings seems, to us, a likely descendant of these puddings as they were originally prepared.

You must be logged in to post a comment.