As the end of November approaches each year, I get increasingly excited about two things: Thanksgiving turkey and the annual re-run of the “Poultry Slam” episode of This American Life. Like it or not, November and December are the very height of poultry season. Unsurprisingly, there are lots of recipes for cooking poultry in Penn manuscripts from making chicken pot pie and fried chicken (two ways) to numerous instructions for roasting.

When I cooked this recipe last Tuesday it was raining in southern California. It was a major news event out here. It was also one of the first dark, chilly, and damp days I’ve seen in ages. I decided to try a recipe “to make a Brown Frickasey” from MS Codex 252 and it was a perfect dish to warm the house and the belly.

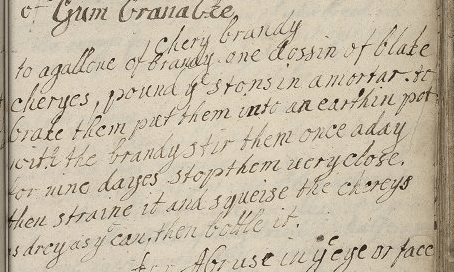

The Recipe

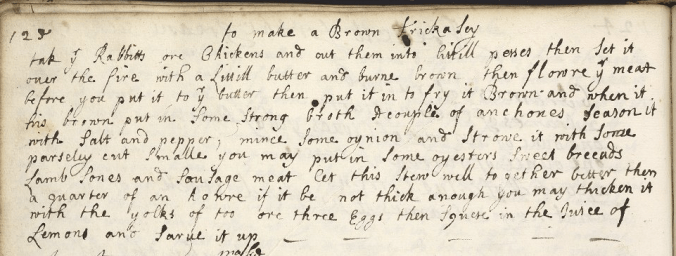

to make a Brown Frickasey

tak the Rabbits ore Chickens and cut them into littill pesses then set it

ouer the fire with a Littill butter and burne brown then flowre the meat

before you put it to the butter then put it in to fry it Brown and when it

tis brown put in some strong broth A couple of anchoves season it

with salt and pepper, mince some oynion and strowe it with some

parseley cut smalle you may put in some oyesters sweet breeads

Lamb sones and sausage meat let this stew well together better then

a quarter of an howre if it be not thick enough you may thicken it

with the yolks of too ore three Eggs then squese in the Juice of

Lemon and sarue it up

This is a simple and delicious recipe with lots of room for variation: Brown a delicious mix of meats in butter then add more meat, stock, and flavors. Ken Albala’s Cooking in Early Modern Europe, 1250-1650 describes a fricassee as a method for frying meat and adding a flavorful sauce. As this recipe demonstrates, it is a very flexible method that works well with poultry and other meats. I decided to use chicken breasts, pork sausage, and chicken stock, but I also could have faithfully followed this recipe using rabbit, oysters, sweet breads, or other offal.

Our Recipe

3-4 T butter

2 chicken breasts, sliced into 2-inch strips

4 T flour (for coating chicken)

1/2 lb. pork sausage meat (either sausage removed from its casing or sausage meat sold uncased)

1 onion, medium sized, chopped

4 anchovies, chopped

1 1/2 -2 c chicken broth

salt and pepper (to taste)

the juice of half a lemon

2 T chopped parsley

Lightly flour the chicken strips by rolling them in a plate or bowl of flour. Finish chopping the onion and anchovies and readying the sausage meat . Make sure your stock is also ready to go if you’re defrosting it or using a concentrated boullion preparation.

In a dutch oven or large pot, heat the butter until it melts, smells nutty, and starts to darken in color. Add the strips of floured chicken slowly. Don’t worry if all the chicken doesn’t fit at the beginning because the strips will shrink as they cook. Turn the meat over so that it cooks on both sides. When the outside of the chicken starts to brown, add the sausage meat and cook for 1 minute. Add the chopped onion and anchovies and cook for 1 minute more.

Add the broth and simmer uncovered for 15-20 minutes. When the gravy is thick and everything is well cooked, squeeze the juice of half a lemon into the stew. Sprinkle parsley on top. Serve hot.

Results

My spouse and I devoured this delicious stew with some roast butternut squash, kale salad, and a bottle of fine, west-coast IPA. It was warming and satisfying meal. We both picked additional mouthfuls of sausage-y chicken out of the pot after we’d cleaned our plates.

I started by browning 2 T butter and added about 2 more as the chicken cooked. The sauce thickened into beautiful gravy on its own. I used homemade chicken stock that I (try to) always keep in my freezer. Homemade stock from pork bones would also be a delicious addition. Store-bought or concentrated stocks will work well here, too. But be sure to taste the mix before adding additional salt.

I can see how this method of preparation would work well for a variety of poultry and other meat. The strips of chicken stayed tender and flavorful, but this would be great with dark meat chicken. I used peppery pork breakfast sausage meat from a local farm. I think a pork and sage or even a pork and apple sausage would work well here. Finally, the anchovies added an unexpected note that was more umami than fishy. I suggest that you give them a try if you’re an anchovy skeptic, but not if you absolutely despise these small, flavorful fish. The lemon adds an essential bright note that complements the fat and savory flavors of the dish.

You must be logged in to post a comment.