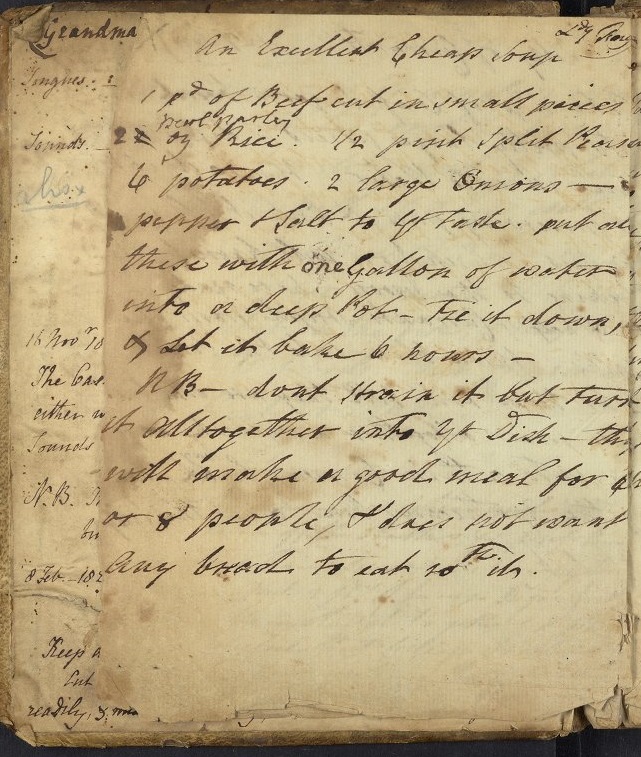

This recipe has been on my mind for a while. What are Artificial Potatoes? And WHY are they? I wanted to solve the mystery of the Artificial Potatoes. (The Mystery of the Artificial Potatoes: title for my first novel?) I couldn’t quite imagine from the recipe even what they would look or taste like, which is the perfect justification for a culinary experiment.

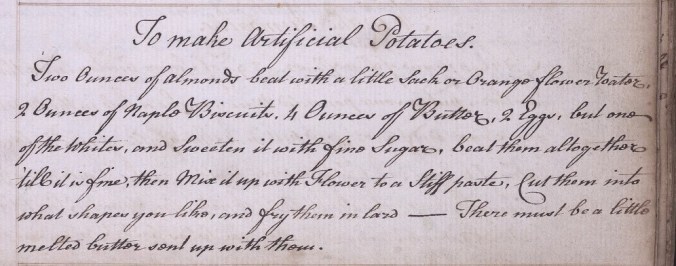

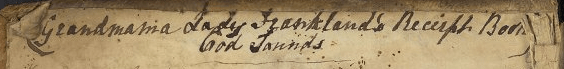

This recipe comes from Ms. Codex 1038, home to one of my favorites thus far: the Desart Cakes (which I mentally pronounce as “DeSART Cakes,” just because it’s fun). This is one of the first recipes in the book. Potatoes were introduced into England by the late seventeenth century, so the writer of this late-eighteenth-century recipe would have been familiar with “real” potatoes.

While we frequently notice recipes that crop up across multiple cookbooks (particularly for puddings), we haven’t come across another one for Artificial Potatoes. Curious, I ran a search through Eighteenth-Century Collections Online, an invaluable digital database of texts published between 1700 and 1800. And I found something interesting. Even with variant searches, only one recipe for Artificial Potatoes comes up, in Eliza Smith’s The Compleat Housewife: or, Accomplish’d Gentlewoman’s Companion (1742, 11th ed.; the recipe appears through the 18th ed., 1773). While I’m sure there are other Artificial Potatoes recipes out there in manuscript and in print, this scarcity is striking. Our manuscript recipe is worth comparing with Smith’s:

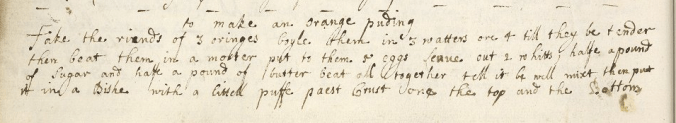

Artificial Potatoes for Lent: A Side-Dish; Second Course.

Take a pound of butter, put it into a stone mortar with half a pound of Naples-bisket grated, and half a pound of Jordan almonds beat small after they are blanched, eight yolks of eggs, four whites, a little sack and orange-flower-water; sweeten to your taste; pound all together till you don’t know what it is, and with a little fine flour make it into a stiff paste, lay it on a table, and have ready about two pounds of fine lard in your pan, let it boil very fast, and cut your paste the bigness of chesnuts, and throw them into the boiling lard, and let them boil till they are of a yellow brown; and when they are enough, take them up in a sieve to drain the fat from them; put them in a dish, pour sack and melted butter; strew double-refin’d sugar over the brim of the dish.

(E[liza] Smith, The Compleat Housewife [London, 1742, 11th ed.], 131-32)

That Smith identifies these Artificial Potatoes as a Lenten dish is intriguing. I don’t know of a reason why real potatoes might be off-limits during Lent, or why these fried dough balls should be particularly suited to Lent. (Any insights are welcome!) It’s also good to note that Smith identifies these as “a Side-Dish; Second Course” – not, in other words, as dessert. What we might think of as a dessert because of its ingredients (ground almonds, biscuit crumbs, sugar, flower water) wasn’t necessarily so for eighteenth-century eaters.

Smith’s recipe raises another question: what should these Artificial Potatoes look like? I assumed that they would be small and round, like new potatoes, “the bigness of chestnuts,” as Smith’s recipe directs. But the Ms. Codex 1038 recipe writer directs the cook to “Cut them into what shapes you like,” which sounds more like a flat roll-out cookie. As we’ll see, I tried both ways. But before shaping the Potatoes, I had to gather the ingredients.

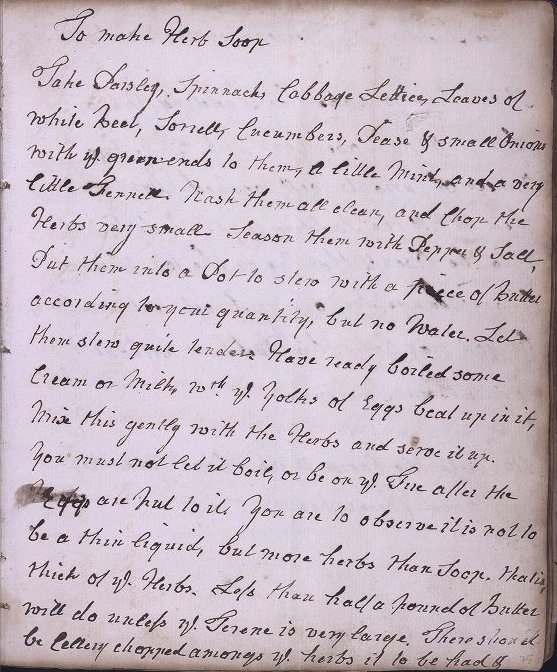

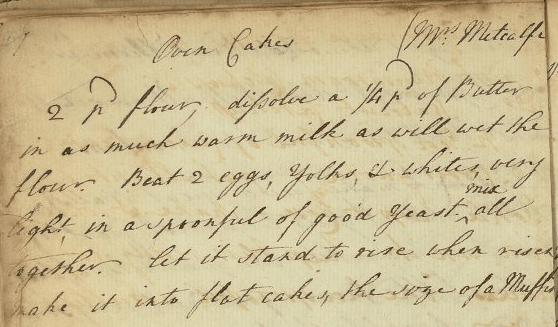

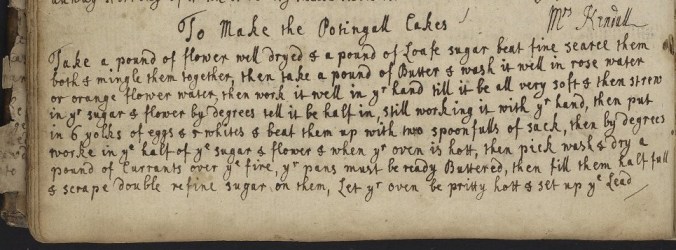

Recipe within a Recipe: Naples Biscuits

As if these Artificial Potatoes weren’t mysterious enough on their own, they required some additional sleuthing for one of their ingredients. The recipe calls for “Naple Biscuits,” or Naples biscuits, but doesn’t provide a recipe. Research time! Naples biscuits are rosewater-flavored dry biscuits baked in small rectangular tins, similar in texture and size to our ladyfingers. Naples biscuits feature in a range of early modern recipes – for puddings, mince pies, even a possett drink. (Biscuit-crumb-enhanced cold possett? We might need to try that one.) They’re typically grated into crumbs and used as a thickening agent rather than left whole. But how to make them? Ms. Codex 1038 doesn’t contain a recipe, so I turned again to ECCO to search for Naples biscuits (or biskets). Interestingly, while a lot of eighteenth-century cookbooks call for Naples biscuits, sometimes in as many as eight recipes, they almost never include a recipe for them. My search yielded only a few recipes. This suggests either that the basic recipe was so well-known that it didn’t need to be given or, more likely, that cooks would buy Naples biscuits already made, just as we often do with ladyfingers.

I used Elizabeth Cleland’s New and Easy Method of Cookery (1759) for reference:

To make Naples Biscuits.

Take a Pound of fine Sugar pounded and sifted, a Pound of fine Flour, beat eight Eggs, with two Spoonfuls of Rose-water; mix in the Flour and Sugar, then wet it with the Eggs, and as much cold Water as will make a light Paste; beat the Paste very well, then put them in Tin Pans. Bake them in a gentle Oven.

(Elizabeth Cleland, A New and Easy Method of Cookery [Edinburgh, 1759])

My version, which halves Cleland’s:

4 eggs

1 tbsp. rosewater

1/2 lb. sugar

1/2 lb. flour

Beat eggs and rosewater (by hand or with a mixer) until frothy; add sugar and flour and beat thoroughly, until lighter in color and very well blended. If dough seems too heavy or dry, add 1 tsp. cold water at a time. (My batter held together nicely at this point, similar to a pound cake batter. Since another Naples biscuit recipe I looked at didn’t call for the addition of cold water to thin the batter, I left it out. I might try it next time to see if the water produces a slightly lighter biscuit, but these turned out just fine.)

Bake in greased madeleine pans, filled with 2 tbsp. batter each, for 14 mins. at 350F. They should be firm to the touch, lightly browned around the edges and on the scalloped bottoms, but the tops won’t have much color. Turn onto a wire rack and cool completely. Makes 20 madeleines. (Mini-muffin tins would also work.)

These Naples biscuits aren’t showstoppers, and they don’t clamor to be eaten by themselves, though I nibbled on one while making the Artificial Potatoes. They’re dense, dry, and nicely rosewater-y, and that’s about it. I understand why they were used more often as ingredient than eaten as a stand-alone treat.

The Main Recipe

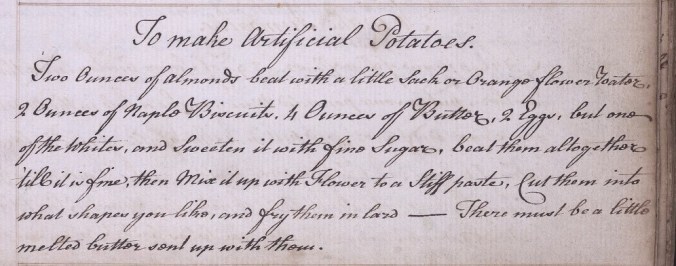

To make Artificial Potatoes.

Two Ounces of Almonds beat with a little Sack or Orange-flower Water,

2 Ounces of Naple Biscuits, 4 Ounces of Butter, 2 Eggs, but one

of the Whites, and Sweeten it with fine Sugar, beat them altogether

’till it is fine, then Mix it up with Flower to a Stiff paste, Cut them into

what shapes you like, and fry them in lard — There must be a little

melted butter sent up with them.

Our Recipe

2 oz. (heaping 1/2 c.) ground almonds

2 oz. Naples biscuits [2 madeleines], grated or pulsed in a food processor into crumbs*

3/4 c. flour

4 oz. (1 stick) butter, softened

4 tbsp. sugar

1/2 tsp. orange flower water (optional; you could also use sherry or rosewater)

1 egg

1 egg white

oil for frying**

Combine dry ingredients (almonds, biscuit crumbs, flour) and set aside. Cream the butter and sugar, then add the orange flower water, egg, and egg white and mix until well-combined. Dough should hold together and be soft but not too sticky.

Shape dough in one of two ways:

1) Cut or pinch off about a tbsp. of dough and roll it in your hands until fairly round. Repeat. (I also flattened these round balls slightly for one round of frying; they cooked through somewhat better.)

2) Chill dough for 10 mins. to let it firm up a bit, then roll it out on a floured board to about 1/4″ thick; punch out rounds with a cookie cutter. Smaller rounds (1.5 to 2″) are best.

-

-

Naples biscuit crumbs

-

-

chilled dough

-

-

Option 1: patted into rounds

-

-

Option 2: rolled and cut out

Line a plate with paper towels. Heat 2 tbsp. oil (see **Note) in a skillet at medium-high heat and fry the Potatoes in batches, giving them a few minutes on each side, until golden-brown. As the Potatoes are done, place them on the lined plate to absorb excess oil. I didn’t think they needed the flourish of extra melted butter on the side, but then again, melted butter never hurt anything.

-

-

balls, fried in butter

-

-

flat shapes, fried in oil

-

-

balls (L) vs. slightly flattened balls (R)

*Note on pulverizing the biscuits: I grated mine on a box grater, but since the edges are quite hard, the process was pretty messy and I ended up with uneven crumb size (powdery from the edges, larger from the softer centers). I’d use a food processor next time.

**Note on frying: The original recipe calls to fry the Potatoes in lard, but I don’t exactly keep lard on hand. I fried the first batch in butter, which gave them a lovely browned-butter taste … until, of course, the butter solids started burning. I switched over to oil and had more success. So, fry in your preferred fat.

Clockwise from left: round ball, flattened ball, cut-out round

The Results

As sometimes happens with long-anticipated recipes, these were somewhat underwhelming. I’m still not sure what they should look like: it makes the most sense that they would look like small potatoes, but rolling and cutting them out bakes them more thoroughly and avoids a doughy center. Whatever shape, taste-wise they’re fairly bland. They’re also slightly greasy from being fried; I might actually try this recipe again but bake the rounds, just to see if they would work as cookies.

However, this experiment has taken the edge off my Artificial Potato curiosity. And now I have more than a dozen Naples biscuits in my freezer just waiting to thicken more dishes down the line.

You must be logged in to post a comment.