Not all recipes are original. Flipping through MS Codex 785 I was intrigued by this recipe for “Lemmon Cakes.” These lemony sweets are candies, not cakes! But with a little research into the recipe’s ingredients and methods (fair water? candy height? sleek’d paper?) I located its origin: This recipe is a verbatim transcription from Hannah Woolley’s cookery book The Queen-like Closet or Rich Cabinet: Stored with all manner of Rare Receipts For Preserving, Candying and Cookery. Very Pleasant and Beneficial to all Ingenious Persons of the Female Sex (1670).

Woolley was already known for her earlier cookery books and this one was reprinted a few times in the last decades of the seventeenth-century. (The full text of the second edition is available here.) It also seems to have been a common book in early American kitchens (more on this here). Woolley’s recipes were certainly a touchstone for cooks in the early decades of the eighteenth-century when this manuscript was most likely compiled. Moreover, our manuscript compiler not only copied the recipe for Lemmon Cakes, but also for a range of other recipes for preserves, biscuits, and other dishes. In the early sections of the manuscript the order matches Woolley’s exactly.

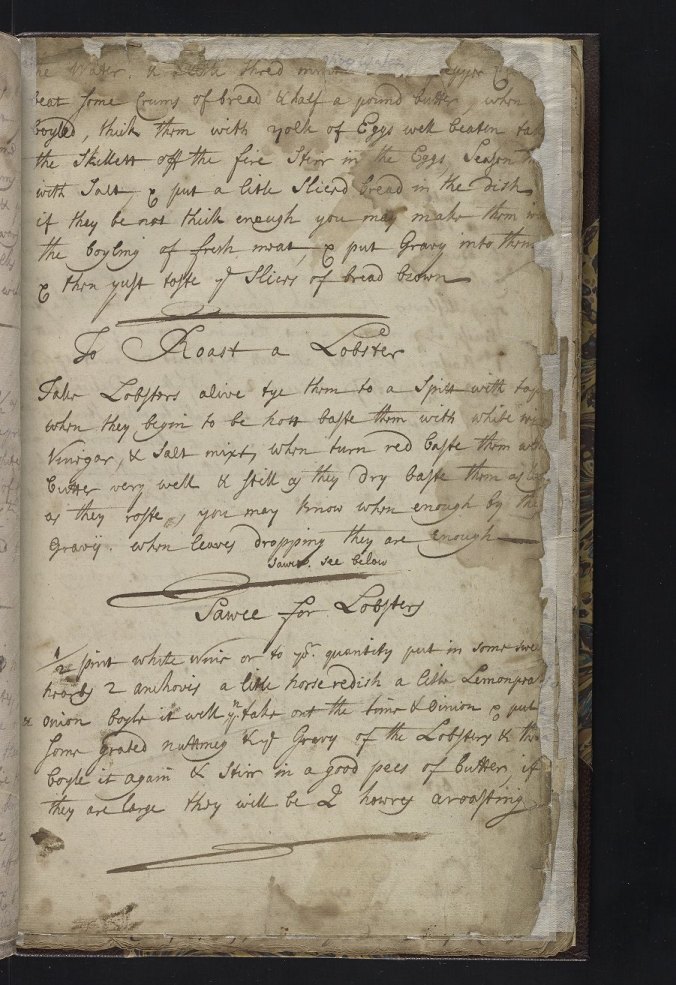

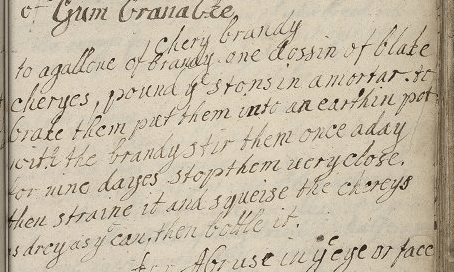

It is not uncommon for manuscripts materials in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to include substantial extracts from printed works. Recipe books are no exception. MS Codex 785 is an intriguing patchwork of recipes from an array of sources, some that I plan to track down soon.

The Recipe

To make Lemmon Cakes

Take half a pound of refin’d sugar, put to it –

two spoonfulls of Rose water, as much Orange

flower water and as much fair water, boil to a –

Candy height, then put in the Rine of a Lemmon

grated, and a little Juice, Stirr it well on the

ffire, and drop it on plates or sleek’d paper.

Our Recipe

Our recipe is very similar. As I mentioned above, with some basic searching it became clear that “fair water” is a synonym for “clean water”; “candy height” is the moment when the sugar is dissolved but begins to re-form crystals on the sides of your pan; and “sleek’ed paper” is made “slick” in preparation for the hot candy. Woolley also includes a recipe for “plates” or wafer-like bases for candies.

1/2 lb sugar

2T rosewater

2T orange blossom water

2T water

zest of one lemon

juice of half a lemon

baking parchment (or other appropriate surface)

(I made a half batch.)

Put the sugar, scented waters, and water into a small saucepan. Heat until the sugar is melted and crystals begin to form on the side of the pot. Add the lemon zest and juice. Heat through and stir.* Pour candy mix onto baking parchment to set. Cut, break, or use another method to shape bite-size candies.

The Results

I am not a skilled candy-maker: I messed up on this one. My “lemon cakes” were more of a caramelized, sweet, lemony brittle. They were relatively tasty to suck on like a lozenge, if in a tangy (partially burned) sort of way. If you know how a thing or two about working with hot sugar, or a least own a candy thermometer, you may fare better with this recipe. I’d be curious to see how other citrus or floral waters and zests would flavor these candies.

Regardless, I’ll be coming back to more recipes from MS Codex 785 and Hannah Woolley’s cookbooks.

*This is the point in the recipe where I think a candy thermometer (or skill) might help.

You must be logged in to post a comment.