Earthy sage flavors this tender, savory pudding. Last weekend I had the pleasure of cooking it in the bake oven at Pottsgrove Manor with the help of Ann Mumenthaler and in dialogue with a wonderful group of guests at our collaborative cooking event.

As always, the recipe that I’ve written below is ready to use in your home kitchen. That said, I’m still mulling over what I learned from preparing this recipe (and Locke’s pancakes) using historical techniques and equipment.

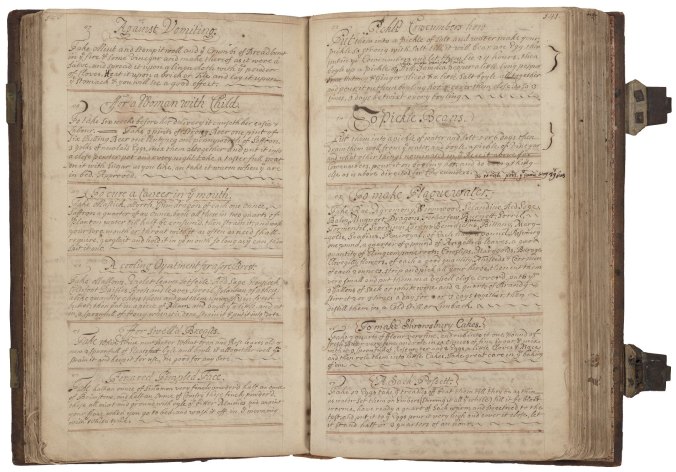

The Original Recipe

Take your sage & put em to boyle on the fire with watter, & when it has

Colloured the watter, or the sage is almost Enough, then take the sage

and boyle em in milk, & lay a litle flower to boyle in the milk, then when

it is boyled Enough, set it to coole, & when it is coole Enough, Mix Eggs

and Milk as you would for a Custard Pudding, & then put in your sage

and be sure to butter the bottome of your Dish, & sett butter up & Downe

the top of your Pudding, and then put it in the oven, and take care you

doe not over bake it, a spoonful of sack will make the Pudding very

good, or plague watter, soe as you Doe not put to much, it will be very

pretty, & you may put Lemon or Orange in it,

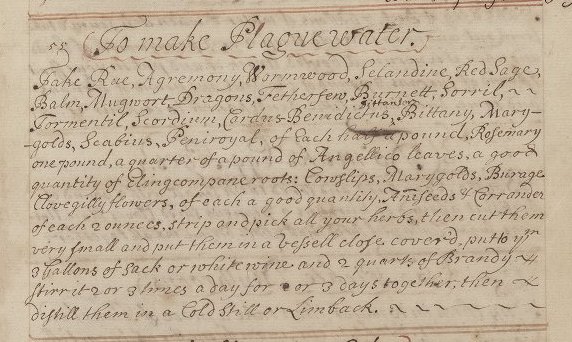

The recipe intrigued Ann and I for a number of reasons. First, it’s from Merryell Williams’s recipe book that was used and compiled in the seventeenth century and is now held at the National Library of Wales, Peniarth MS 513D. This is a very interesting, fully-digitized recipe book that I’m planning to spend more time with in the coming months. Second, we were curious about whether sage pudding would be more savory or sweet. The recipe does not call for any sugar, but the added flavorings of sack (fortified wine like sherry), plague water, and lemon or orange could take it in an array of directions (especially if the lemon or orange were candied peel sprinkled on top). Finally, we were curious about the use of plague water as an optional flavoring. I’ve written about plague recipes here before (and also in this co-written article). While plague water was a shelf-stable tonic made from alcohol and herbs, usually rosemary, and would have been readily to hand in elite households in this period, I have never seen it mentioned in a culinary recipe before. We wondered if the plague water, like the sage, was intended to convey medicinal benefits as well as flavor to the finished dish.

Then there was the matter of deciding how to prepare this recipe at home and in the bake oven. I took the instruction “as you would for a Custard Pudding” as my guide and I consulted Karen Hess’s work to review some contemporaneous custard recipes. Hess suggests baking custard puddings like this one in a bain-marie to preserve the tender texture and avoid overbaking. This method worked well both in my home oven and in the bake oven at Pottsgrove Manor. However, we also tested some small puddings in the bake oven without using a bain-marie and found that they were also delicious and had an interesting contrast between the crust and the interior. In my updated recipe below, I provide directions for the bain-marie method, but I believe that this sage pudding could also be baked on its own. The cook will simply have to watch for that distinctive jiggle that demonstrates that the custard is set, but not overdone.

Updated Recipe

2 cups water (plus more for the bain-marie)

½ cup of sage

2 cups milk

½ cup flour

2 eggs

1 tablespoon sherry

2 tablespoons butter

Put the sage and water in a pot and bring to a boil for approximately 5 minutes. When the water is a pale green color, remove the pot from the heat and pour off the water. Keep the sage in the pot and add the milk.

Bring the milk and sage to a low boil. Remove from the heat and stir in the flour. Whisk the mixture until there are no clumps. Set aside to cool.

While the infused milk is cooling, preheat your oven to 350F. Fill a kettle with water and bring it to a boil. Butter a glass or ceramic baking dish in which you plan to cook your pudding. Identify a larger, second baking dish that can hold the pudding dish and a few inches of water.

Stir the eggs and sack into the infused milk and flour mixture. Pour this mixture into the prepared baking dish. Add pieces of butter to the top of the pudding.

Place the pudding dish in the larger baking dish to set up your bain-marie. Fill the area around the pudding dish with warm water. Ideally the water will be a similar height to the custard itself, but not spill over into the pudding dish.

Bake for 40 minutes. A tester should come out clean, but the pudding should still jiggle in the middle.

Serve warm.

The Results

The sage pudding has a gorgeous, yielding texture. I can imagine eating it alongside roast lamb. I can also imagine a sweet version of this pudding either sprinkled with candied citrus peel or with sugar stirred in before cooking. If you try this recipe with plague water or citrus or even sugar, or if you bake it without a bain-marie, please let me know!

You must be logged in to post a comment.