This post was written by Marissa Nicosia and Sarah Peters Kernan. Sarah, a culinary historian, is co-editor of The Recipes Project and host of the Around the Table podcast.

When Sarah and I realized that we had a shared interest in Lady Anne Percy’s recipe book, we decided to try out a recipe for a kind of cookie, called a cracknell, that we both found very curious: “To make the Lady Duthes Crakenles.”

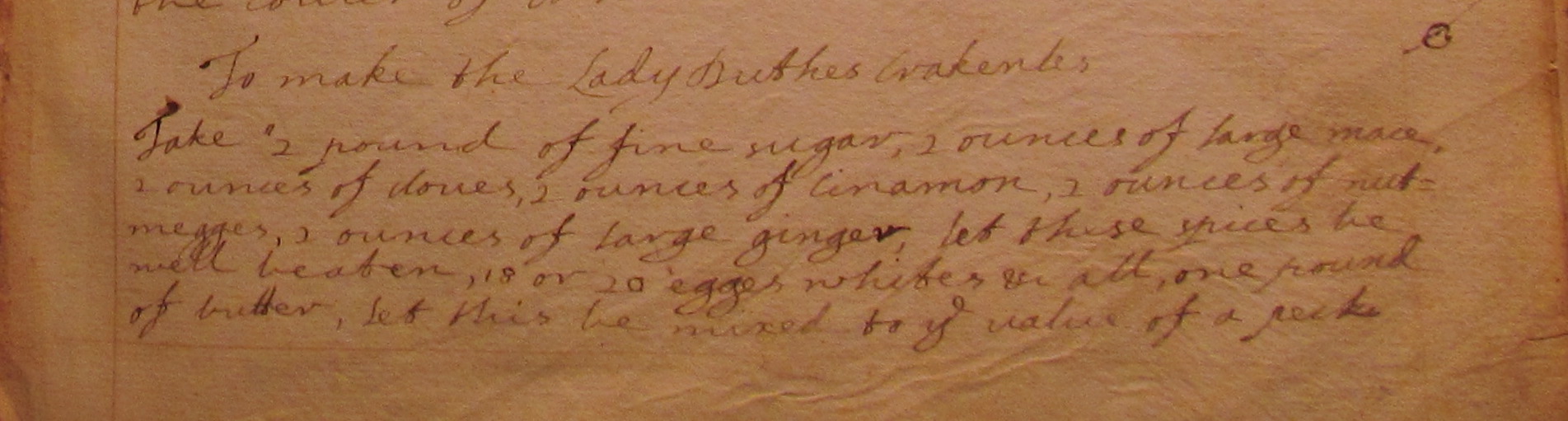

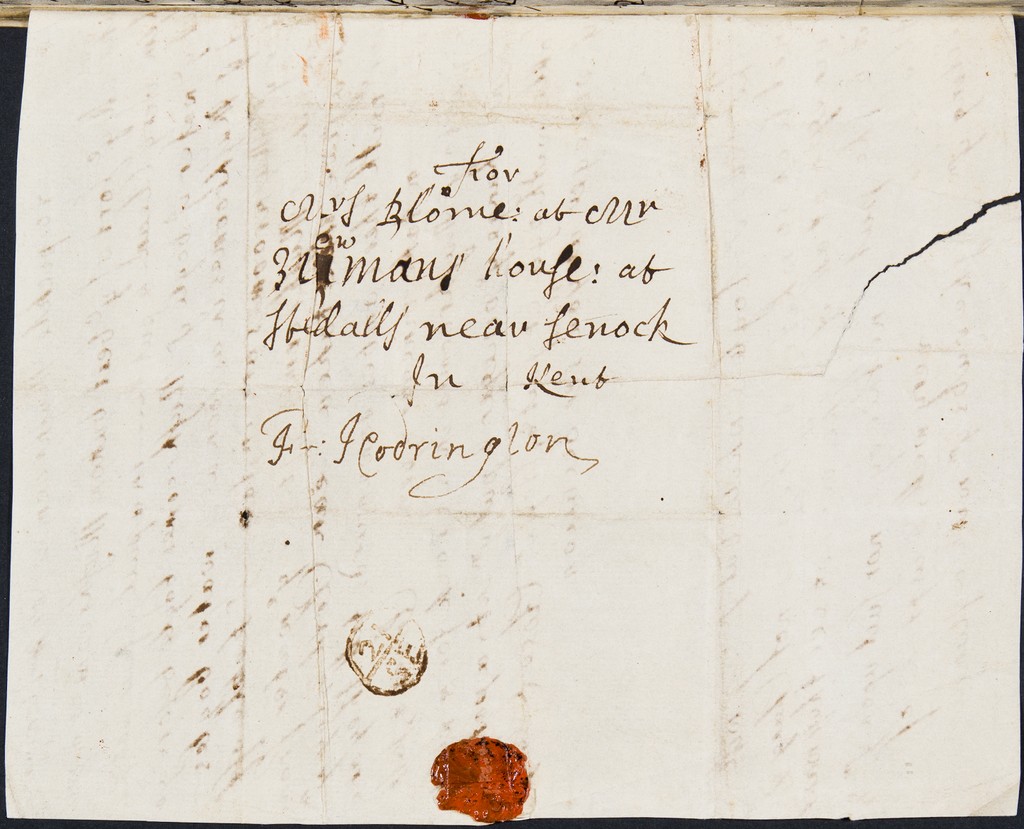

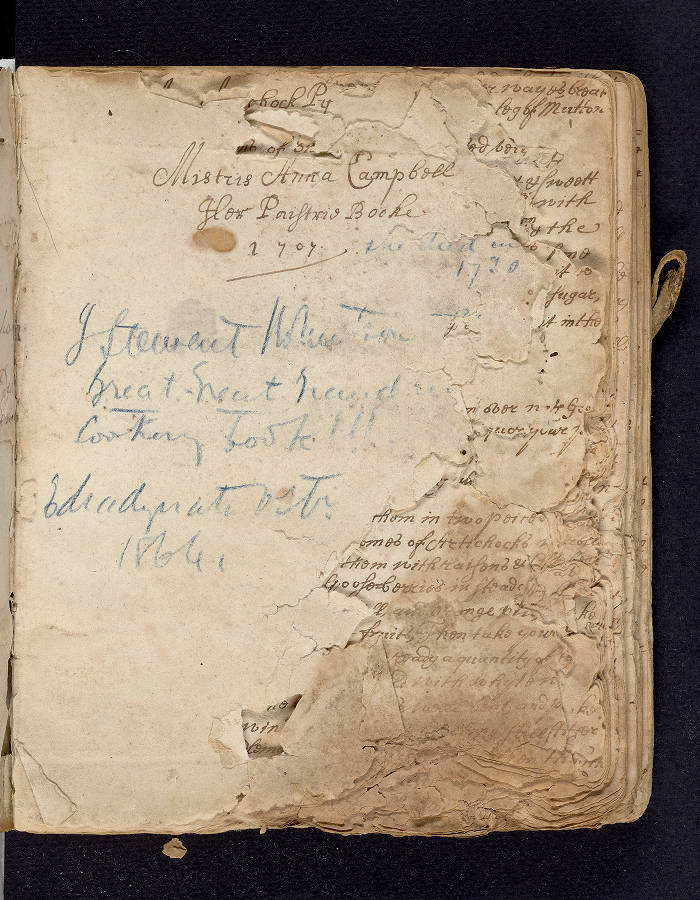

A teenaged Lady Anne Percy copied her mother’s recipes into her recipe book in a distinct hand with a mix of italic, roundhand, and secretary features around 1650. Philip Lord Stanhope, her husband, writes a note inside the front cover of this manuscript to tell us that it is her hand and that these are her family recipes. Remaining in her husband’s family’s library for generations, the undigitized manuscript, Whitney MS 2, is now part of the Whitney Cookery Collection in the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division. It contains a variety of culinary, confectionary, medical, and household recipes. This recipe is one of three cracknell recipes in the manuscript.

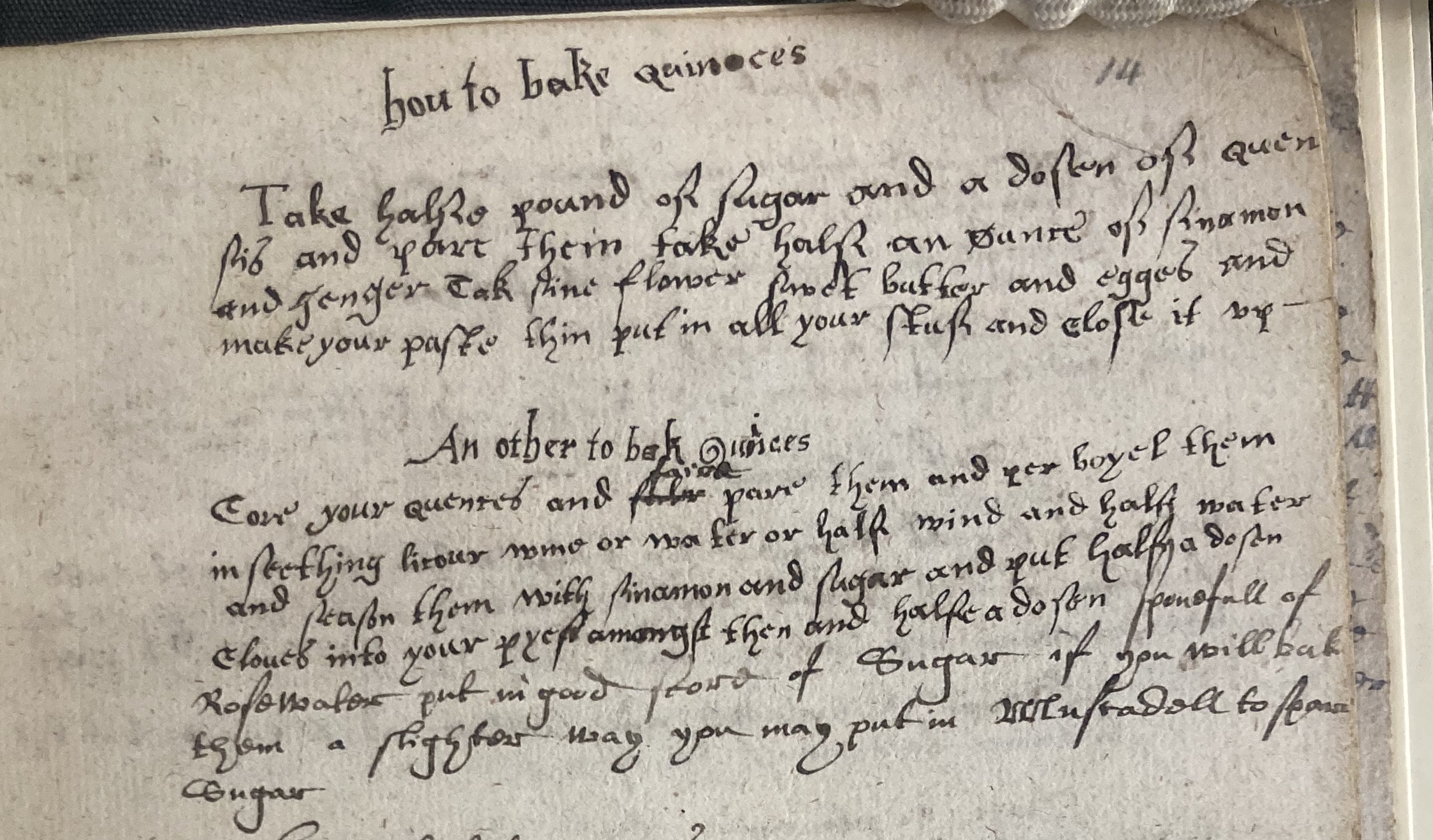

What exactly are cracknells? They are cookies, sometimes spelled cracknel or cracknell, and they appear frequently in early modern English cookbooks and recipe books. Despite their constant presence, cracknells actually changed quite a bit over three hundred years.

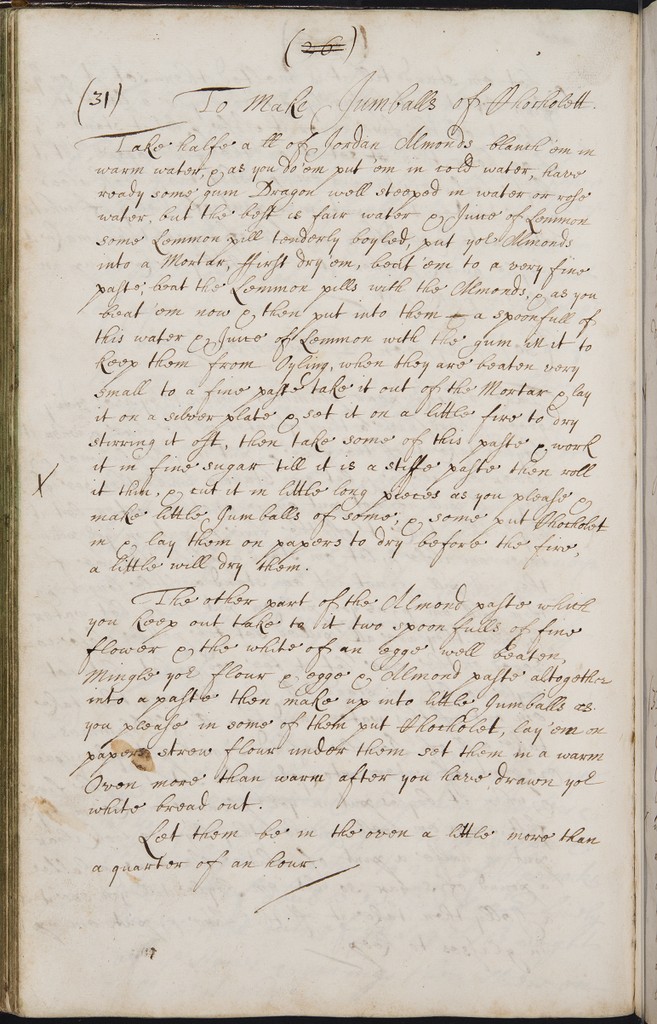

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, cracknells were boiled prior to baking. This is the type of cracknell recipe included in Lady Anne Percy’s recipe book. These cracknells have an outer layer that cracks when you bite into it but depending on exactly when you are eating it and what type of baking and drying method you use, it might be dry and crisp on the interior, or slightly chewy. The cookie, however, should not be tough or heavy. These cracknells were usually spiced and slightly sweetened, and some recipes included ingredients like wine or yeast in the dough. A seventeenth-century recipe from a manuscript at the Folger Shakespeare library describes shaping cracknells by rolling dough “vpon a smooth table with your hands into little long roules, and make them into knotts as you doe iumballs, or what fashion you will.” This older cracknell form has much in common with Italian tarelli, another boiled-and-baked treat still available today.

During the seventeenth century, English cracknells began to change into a very different type of biscuit. As Stephen Schmidt describes in detail, these new cracknells were very thin, crisp cookies and did not involve any boiling prior to baking. These thin, unboiled cracknells became the standard form of the recipe in England by 1700 and remained in circulation for at least another century.

In what follows, we include a transcription of the original recipe and our two different recreation attempts – one with white wine and one with red wine – as well as our tasting notes. Let us know if you try these and what you think!

Original Recipe

To make the Lady Duthes Crakenles

Take “2 pound of fine sugar, 2 ounces of large mace,

2 ounces of cloves, 2 ounces of cinamon, 2 ounces of nut=

megges, 2 ounces of large ginger, let these spices be

well beaten, 18 or 20 egges whites & all, one pound

of butter, let this be mixed to ye value of a peck

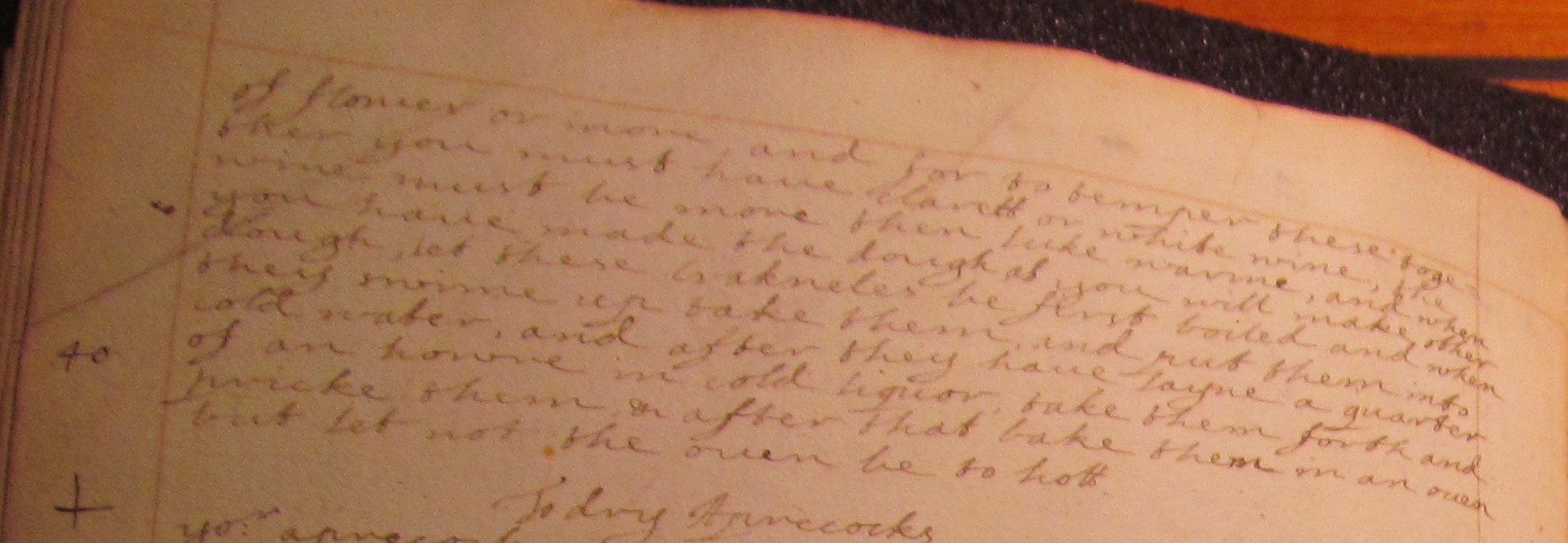

of flower or more, and for to temper these toge

ther you must have clarett or white wine, the

wine must be more then luke warme, and when

you have made the dough as you will make other

dough, let these crakneles be first boiled and when

they swime up take them, and put them into

cold water, and after they have layne a quarter

of an howre in cold liquor, take them forth and

pricke them, & after that bake them in an oven

but let not the oven be to hott.

SK Updated Recipe

⅛ of original recipe with white wine

Ingredients

½ cup sugar

1 ½ teaspoon ground mace

1 ½ teaspoon ground cloves

1 ½ teaspoon ground cinnamon

1 ½ teaspoon ground nutmeg

1 ½ teaspoon ground ginger

2 eggs, gently beaten

4 Tablespoons unsalted butter (at room temperature)

3 ¾ cups all-purpose flour

1 cup white wine

Instructions

Preheat oven to 325 F.

Bring a large pot of water to a gentle boil.

Heat the wine over low heat in a pan on the stovetop. Do not boil! The wine should be warmed just “more than luke warme.”

Prepare a large bowl of cold water.

Combine the sugar, mace, cloves, cinnamon, nutmeg, ginger, and flour. Mix together until well combined.

Add the eggs, butter, and warm wine to the flour mixture. Begin mixing together with a wooden spoon. The mixture will seem very shaggy at first.

Once most of the mixture is combined in the bowl and forming into a single ball of dough, turn out the dough onto a flat surface and knead together with your hands for 1-2 minutes. The dough will come together quickly and form into a smooth ball. The dough will not feel sticky at all. You will not need any additional flour on your kneading surface.

Form the cracknels.

Option 1: To form knots

Cut the dough into 64 same-sized pieces using a bench scraper or knife. Roll each piece into a 3-4 inch cylinder and overlap the bottom edges. Pinch the area where the dough overlaps so the cracknell keeps its shape.

Option 2: To form circles

Roll out the dough flat, measuring about .25 inch high. Using a circular biscuit cutter or small drinking glass, cut out small circles in the dough. Re-roll the remaining dough and continue cutting out circles until no dough remains. I used a 2-inch biscuit cutter to yield 60 circles.

When you have formed the cracknells, place approximately a quarter of them into the gently boiling water. Do not overcrowd the pot, or some could stick to each other. Gently stir so they do not stick to the bottom. Once they begin rising to the top (about 1 minute 30 seconds-2 minutes) remove them with a slotted spoon or spider and place them into the bowl of cold water. Repeat with the remaining cracknells.

After the cracknells have sat in the cold water for 15 minutes, remove them and gently dry them off with a clean, dry kitchen towel. Prick each cracknell several times with a fork.

Place the cracknells on two baking sheets lined with parchment paper or Silpat. Then, place the sheets into a preheated oven. Bake for 325 F for 30 minutes. Then, without opening the oven, change the temperature to 250 F and bake for an additional 60 minutes.

Tasting Notes

These are delicious slightly warm or just cooled with coffee. I recommend eating them the same day as baking. While the knots dry out fairly well and still remain light, the circles tend to get tougher the longer they cool.

MN Updated Recipe

1/8 original with red wine

Ingredients

½ cup sugar

1 ½ teaspoons ground mace

1 ½ teaspoons ground cloves

1 ½ teaspoons ground cinnamon

1 ½ teaspoons ground ginger

1 ½ teaspoons ground nutmeg (or 1 teaspoon freshly grated nutmeg – ¼ nutmeg)

4 Tablespoons butter, room temperature

2 eggs, room temperature

3 2/3 cups flour

1 cup red wine

Instructions

Set up a wide saucepan filled ¾ of the way with water. Cover and bring to a boil.

Pour the wine into a small saucepan. Warm until it just begins to simmer. Cover with the lid and set aside. Use when the wine is still hot to the touch, but not scalding or painful.

While the wine is warming up and then cooling to “warmer than lukewarm”, start the base of the dough. Cream together the sugar, spices, and the butter. When the wine is ready, add the eggs and two cups of the flour to the sugar, spice, and butter mix. Combine well. Add 1/3 cup of the warm wine and stir to combine. Add the rest of the flour and another 1/3 cup of the warm wine and combine. Add the rest of the warm wine a tablespoon at a time if you need it. The dough will be smooth, pliable, and a little sticky.

Shape pieces of dough between 1 teaspoon and 1 tablespoon large into rolls, twists, rings, figure eights, and knots.

Set up a heat-safe casserole or glass storage dish on the side and fill it with cold water. Have thin kitchen towel or some paper towel ready on the side.

Preheat your oven to 325 F.

Prepare a large baking sheet with parchment paper, butter, or baking spray.

Working in batches, drop the shaped cracknels into the boiling pan of water. When the float to the top, take them out with a spoon and put them into the cold water dish. This takes about a minute with the water at a rolling boil. You may need to replenish the cooking water and bring it back to a boil during this stage. You also may need pour off warmed water from the cooling dish and refresh with more cold water.

Let the cracknels soak in the cold water for 15 minutes. Remove from the water and put on a clean kitchen towel or paper towel sheets before transferring to your prepared baking sheet.

Bake for 25 minutes.

Tasting Notes

Rights after baking and cooling these cracknells had a wonderful spice and wine flavor and a chewy interior. It was clear that the boiling step had transformed the surface texture, but the cookies were yielding, not crunchy. The sweetness of the cracknells was nicely balanced with the spice. As they dried out over the next few days, they became increasingly crunchy. They hit their peak deliciousness three-five days after baking, I kept returning to the container to have a few with every cup of tea or coffee.

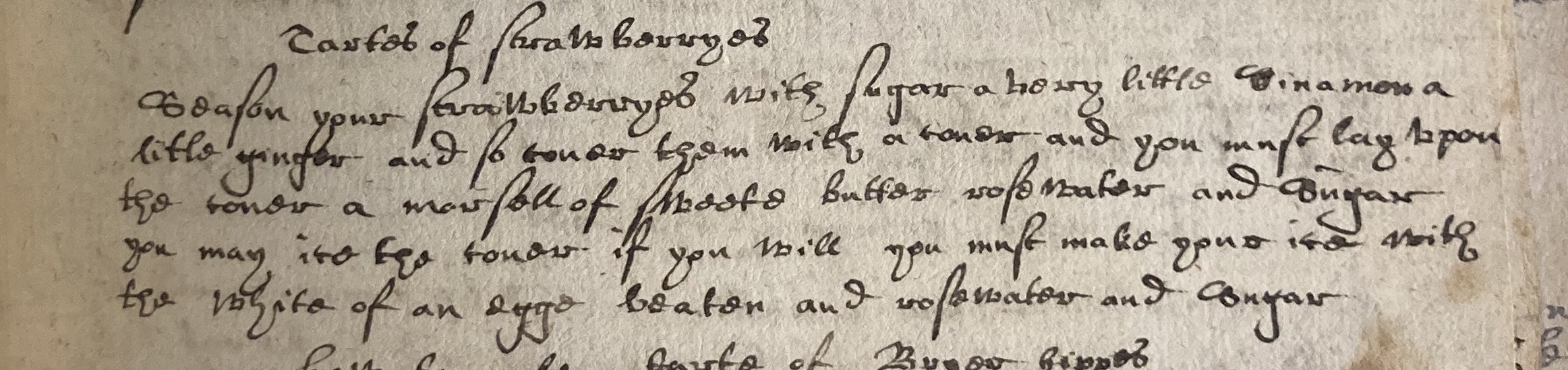

Tartes of strawberryes

Tartes of strawberryes

You must be logged in to post a comment.